Construction Costs Tick Back Up

I served on the Bangor City Council from 2011 to 2020, including two years as mayor of Bangor. People used to sometimes ask me why the city budget went up every year. I would try to respond diplomatically that cities have a lot of pressures on them, and that citizens of all types have expectations of basic services that municipalities are meant to provide, and unfortunately those types of services typically cost more than one might think. In my head, though, I would acknowledge the frustration that city budgets just seem to go up automatically every year. “It just does,” I would say to myself with quiet exasperation.

The former answer is actually accurate. But the latter answer of it just does was always frustratingly true in its own regard too. For a city or town, a large portion of its annual expenses are in personnel, which are generally based on contract negotiations and are typically going to increase by 3-4% annually almost no matter what. But municipalities spend money on other things too — rock salt, playground equipment, vehicles and equipment, repairs to facilities, etc. And unfortunately, the cost of all of that “stuff,” like most goods and services in the overall economy, tends to go up over time.

So too has it been on the construction front for, well, ever. We could talk about tariffs, labor tightness, interest rates, immigration policy, and consumer psychology all day long (and if you’re a regular reader of The Sunday Morning Post, you know that we have). But if you step out of the frenzy of this moment in time and look at construction costs from a 30,000-foot view, the cost of building things increases by about 4% per year, on average, almost no matter what. This statistic comes courtesy of Ed Zarenski of Construction Analytics, who has calculated the 30-year inflation rate in construction expenses for the year ending in 2022 was 3.7%, but if you remove the 2008-2010 period of the Great Recession, the rate is 4.2%, so we’ll call it about 4.0%.

What About Today?

As anyone in the building or construction trades will tell you, not to mention the millions of Americans who were trying to do home construction projects large and small during the pandemic (including those looking to build houses new), the cost of construction soared from 2020 to 2022. This was due to supply chain issues around the world, for sure, but it was also due to roaring demand from consumers, who were suddenly stuck at home, looking inward on their domestic lives and realizing it may have finally been time to replace that deck or to add a home office, etc. A two-year period of dirt-bottom interest rates juiced spending, too, as Americans had a once-in-a-generation opportunity to borrow against the equity in their homes for next-to-nothing, often investing those dollars back into those very same homes through renovations and construction.

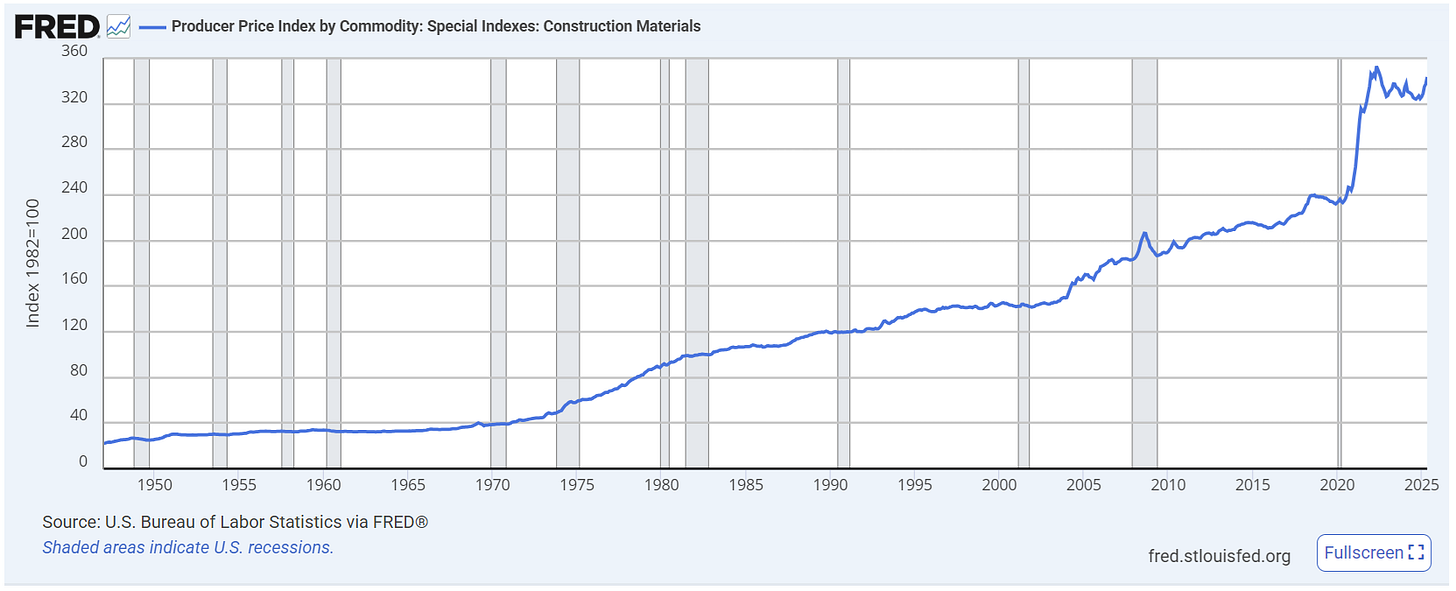

The chart below shows U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data for construction materials over time. This includes both residential and commercial construction, and it is based on the costs to the producer, and not actually the end user (i.e. the homeowner or building owner). But don’t get lost in the weeds on that discrepancy — the chart is a good metric for how the cost of construction materials have changed over time:

As you can see, costs have risen pretty steadily over time. But there is a significant and abnormal jump in 2020. This was the pandemic surge. Per the Construction Analytics article referenced above, “In 2021 [the index] jumped to 8%, the highest since 2006-2007. In 2022 it hit 12%, the highest since 1980-81.” That meant that construction expenses basically jumped 21% over that two-year period, a historically unprecedented surge.

Fortunately starting in the latter half of 2022, things started to settle back down a bit. But sharp-eyed readers of the chart above will note a bit of an uptick at the far-right side of the chart above, which actually represents the past few months of data from where we sit here in 2025. After temporarily normalizing in 2023 and 2024, the cost of construction materials on the producer side is moving back up. Why?

I see four key drivers of the 2025 bump-up in material costs:

Tariffs. It is still too early to have good, clear data on the impact of the Trump tariffs, but the prices of steel and copper both rose about 5% in April alone. The National Association of Homebuilders estimates there will be an increased cost of $7,500-$10,000 on the construction of a new home due to the tariffs. I expect data in subsequent months as it becomes available will start to bear this out.

Global Supply Chain Disruptions. There are a number of serious conflicts around the world right now, most notably in the Middle East and due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. These unfortunate realities have not only disrupted the flow of products to and from these countries around the world, they have also disrupted global travel, particularly through shipping and air travel. As the supply chains become more complicated, so too do the costs.

Tightening Labor Force. As I wrote about earlier in the spring, a crackdown on immigration here in the United States could remove a portion of the labor force in key construction-related industries, such as roofing and drywalling. In addition, both here in the United States and abroad, fewer young people are choosing the trades as a career, which limits the labor pool for construction jobs and specialty contractors. Fewer workers means higher prices for those who are actually still willing and able.

Stockpiling. In anticipation of the new tariffs earlier in the year, many businesses that had the wherewithal to do so started to stockpile materials. The attempt to get ahead of the, say, 25% tariffs on Canadian goods, led to a brief surge in prices as supply met demand, and it also momentarily constricted supply chains due to the abnormally large push of materials in the early part of 2025 ahead of the tariff implementation. That supply chain shock resulted in some higher prices.

What Comes Next?

Unfortunately there is rarely deflation in prices, and when there is, it almost always corresponds with a major economic downturn. It is an interesting thought experiment: would you trade a drop in prices of, say, 10-15%, for an economy in peril with job losses and reduced consumer demand for all sorts of good and services? I have this conversation with commercial borrowers all the time. Yes, it would be great if interest rates were to come down — but the strongest catalyst for a major reduction in rates would be an economic meltdown or some other major geopolitical crisis. People aren’t likely to be able to borrow for a home at 3.0% anytime soon or get a business loan at 4.0%. If the opportunity to do so does come, it will likely be after some major breakage in the economy or some other economic collapse. Could that happen? Of course (but that question is beyond the scope of today’s article!).

One final point: the chart referenced above on the Producer Price Index for construction materials represents the costs of materials to producers. The Producer Price Index does typically correlate to the Consumer Price Index, although they do represent two slightly different things. The PPI is often a leading indicator of the CPI, as producers typically pass the costs along to the consumer.

One way cost increases may be limited on the consumer side is if producers eat the higher costs themselves. That is certainly possible in certain situations, and some CEOs of major corporations have mentioned in earnings calls and elsewhere that they do anticipate absorbing some of the higher costs rather than pass them along to consumers. That might become reality or might just be good PR. In the end, both producers and consumers will likely both continue to eat the higher costs. If you’re in the construction industry, you should be mindful that costs are ticking back up a bit, and if you’re a consumer, you should understand the same. Eventually prices may rise high enough that they outpace demand, and at that point there could be a leveling off even if deflation in prices, as noted above, is not likely.

And one final parting thought, construction budgets especially for large and lengthy projects need to factor in cost inflation. It is not out of the ordinary for significant and complex projects to take a year or more and sometimes even longer to be completed. A $25 million project may turn into a $28 million project if the construction period drags on — so too much a $360,000 new-home construction turn into a $400,000 home.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.