Homes Cost (A Lot) Less 50 Years Ago

Tiny homes increasing in popularity in the face of rising unaffordability

I was analyzing data recently about the surge in home prices over the past year when I happened upon a chart that let me expand the time horizon to see the trend over a much longer period of time. The chart below shows the trajectory of median home prices in the United States going back to 1963:

One of the key takeaways here is that although there have been bumps along the way including, of course, a fairly large and sustained drop over the course of several years leading up to and during the Great Recession, the overarching trend is unequivocally positive: homes have risen steadily in value over the last sixty years and a personal residence has long been a great investment.

That is why it is so important for banks, policymakers, and regulatory agencies to support paths to home-ownership especially for first-time homebuyers and historically under-represented populations including those who have been discriminated against (redlining wasn’t that long ago; more on this in a future article). If certain people or groups are not able to buy into home ownership, they miss out on the lifetime of equity growth that comes from owning a home and the potential for intergenerational wealth as assets are built up and passed along from one generation to the next.

There is just one problem for homebuyers today: prices are sky-high by any metric. Consider this: the median price of a home in the second quarter of 2021 was $374,900. One year ago in the second quarter of 2020 it was $322,600. Ten years ago in the second quarter of 2011 the median home price was $228,100, which itself shows just how much prices have jumped just in the last decade.

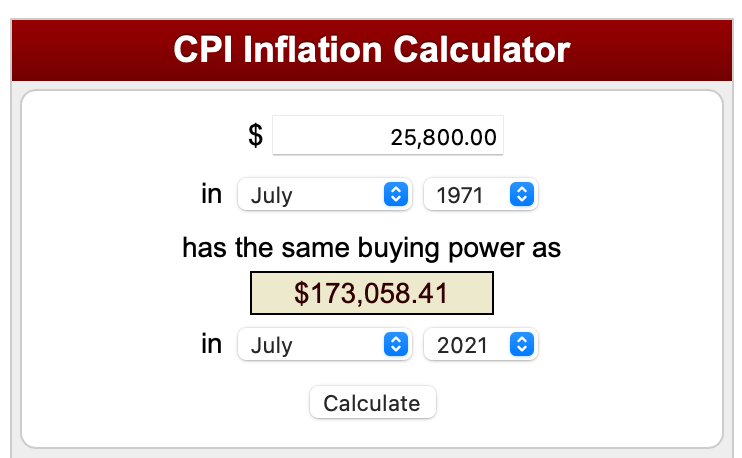

Go back fifty years, however, to the second quarter of 1971. The median price of a home was just $25,800. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ inflation calculator, $25,800 in 1971 in today’s dollars adjusted for inflation would have the purchasing power of $173,058, meaning that today’s median home price of $374,900 is more than double the cost of the median home in 1971 adjusted for inflation. It’s no wonder so many people are priced out of today’s market: there is practically no inventory for low and moderate-income homebuyers right now.

Sears Homes: The American Dream

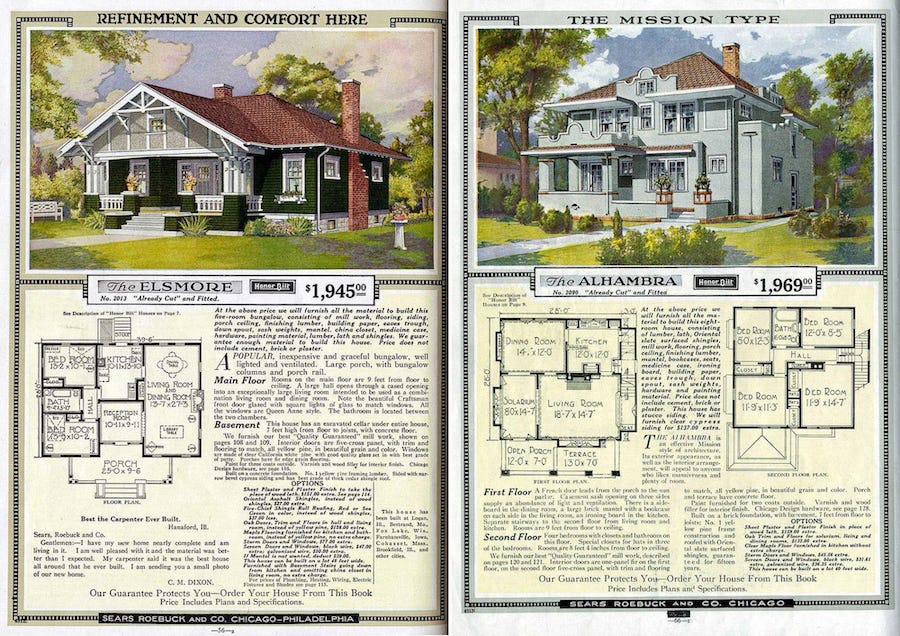

Sears sold over 75,000 homes from 1908 to 1940 (yes, that Sears; the one in bankruptcy whose stores were once ubiquitous in malls and shopping plazas around the country). They did this primarily through catalogue sales. Many of these homes are still standing today and have been comfortably lived in for decades. According to Regina Cole in Forbes, some of the early models in 1918 sold for $3,600-$4,600, which would be roughly $70,000-$90,000 in today’s dollars per the inflation calculator. She writes:

The concept was simple: Customers perused the Sears Modern Homes and Building Plans catalog, picked a dream home from dozens of models, sent a check and, a few weeks later, all the house parts arrived by rail…

…the terms were easy, requiring a down payment of 25% of the cost of the house and lot, as little as 6% interest for 5 years, or a higher rate for up to 15 years. More radically, the application form asked no questions about race, ethnicity, gender or even finances. This made home ownership possible for thousands of buyers who were not welcome at their local banks.

This type of sturdy, affordable home is exactly what helped those 75,000 American families get started on the path to prosperity. These homes were a cornerstone of the American Dream. But imagine trying to pay $70,000 today for all the materials needed for a brand new home. You would be laughed out of the store!

Tiny homes: a possible solution?

It’s not exactly an apples to apples comparison, but a modern version of an economical home that can be delivered and built in a fairly straightforward and speedy way is the increasingly popular “tiny home.” Popularized by TV shows on HGTV, Netflix, and the like, tiny homes have been all the rage over the past ten years. No doubt this is due to both the quirkiness of living in such a small home combined with the marketing and storytelling done by these TV shows. There is also a latent desire among many for minimalism in the face of an increasingly hectic, digital, and corporate world.

An overarching and driving variable in the rise of tiny homes is, of course, also the lack of more traditional affordable homes for low to mid-range buyers.

I spent nine years on the City Council in my hometown of Bangor, Maine before being termed out last November. The concept of tiny homes would come up fairly frequently from well-meaning developers and potential tiny home owners. Tiny homes faced a number of obstacles, however, in that they have not always meet code requirements.

Cities and towns in Maine are required by the state government to use the Maine Uniform Business and Energy Code (MUBEC), which is meant to provide guidelines and consistency between communities. Other states have similar arrangements. MUBEC added provisions for tiny homes in 2017, but with a number of restrictions especially for tiny homes on wheels that can be moved from place to place. As Julie Bayly noted in 2019, these types of dwellings did not quite fit the definition of an RV nor did they fit the definition of a traditional single-family residence. As a result, mobile tiny homes got caught in a donut hole where cities and towns and the state did not know exactly how to regulate them and when that happens, unfortunately, these jurisdictions typically default to more regulation and not less.

Portland, Maine has a helpful document on their municipal website that addresses some of the common questions people have about tiny homes. They offer the following conclusion:

The city [of Portland] is actively looking at the issue of tiny houses and what role they might play in helping address our housing needs. The biggest challenge appears to be the state building code, which the city is required to utilize. We are looking into whether we might lobby for changes in MUBEC to allow more flexibility for tiny homes, but such changes would not happen quickly, and could require legislation.

It now appears that help might be on the way, however, as Maine Governor Janet Mills recently signed a bill into law that puts tiny homes on the same plane as other single-family residences under MUBEC. Julia Bayly recently wrote in the Bangor Daily News that starting this fall the statewide default in Maine will be to allow tiny homes and they will regulated as single-family dwellings. If a city or town does not want to permit them, they will have to write specific local ordinances to exclude them. So perhaps Maine is on the verge of a proliferation in tiny home development, which could help ease Maine’s housing crunch.

A Final Word

Setting aside the concept of tiny homes for a moment, it should be noted that the comparison of a single-family home in 2021 with a home in 1971 or certainly in 1918 is not exactly an apples to apples comparison. Homes today are unquestionably of higher quality. Building materials have improved and the higher quality often means greater expense.

Homes today are also much safer and, increasingly, more environmentally efficient thanks in part to a greater appreciation for modern safety standards and consumer interest in having a lower carbon footprint. Some of those safety standards do result in higher building costs, though, which is one reason why homes cost more today than in previous times. So although traditionalists might disagree (after all, who can knock the grandeur and character of an old home well-built!), the median home of today is generally of higher quality than the median home of previous eras. So in some ways, the much higher median price of a typical American home today makes sense as the buyer is generally getting a higher quality product than he or she or they might have gotten 50 or 100 years ago.

But the fact remains, there is a complete dearth of supply for homes on the lower end of the price spectrum. The median person cannot afford the median home right now. That means that the goal of home ownership is a pipe dream for vast numbers of Americans, especially when you consider that banks’ underwriting standards have generally tightened up due to new regulations and restrictions following the Great Recession, which can make things even harder for first-time homebuyers or under-represented groups.

So what’s the solution? Well, we need more homes. States should look at what places like Maine are doing to loosen up the codes. Cities and towns should follow suit.

Other options to fill the gap in inventory for low to moderate-income buyers include certain types of modular homes, although, to be sure, there are some very high-end modulars out there right now and even though the price of lumber has dropped precipitously, other building materials and the general cost of construction remains high.

Mobile home units in trailer parks are also lower-cost options for a lot of renters and homebuyers. Speaking as a lender, I have seen more mobile home park financing requests come across my desk in the last 12 months than in the previous five years combined. But there are drawbacks to these types of units as well and not everyone wants to live in a mobile home park. Tiny homes, on the other hand, offer more flexibility to choose where you want to live including the potential to actually move the home itself when inspiration strikes.

Clearly something has to give, though. An economy in which a vast number of Americans cannot afford American homes is untenable. There are even stories right now of people buying Tuff Sheds from Home Depot and other comparable products and actually using those as homes. YouTube videos abound with tips on how to convert sheds into tiny homes or how to build a tiny home from scratch.

What comes next? It certainly seems like the trend in tiny homes has momentum and as long as new homes remain unaffordable to vast swaths of Americans, people and their home-buying practices will continue to adapt and evolve. I plan to write on this topic again in the future so if you found today’s article interesting or helpful please make sure you’re subscribed by clicking below and please consider sharing this article to help spread the word. Thanks for reading.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com. Follow Ben on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram and subscribe to this weekly newsletter by clicking below.

Weekly Round-Up

Here are a few things that caught my eye around the web this week:

From Jessica Flint in the Wall Street Journal: young investors are buying homes and rental properties and renting them out as Air BNB’s: https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-vacation-rental-business-is-coming-of-age-11629392453

Copper is slumping. A bellwether or just a correction?

Homes in Austin, Texas are regularly going for $100,000 over asking price:

As the Delta Variant rages, consumer confidence wanes:

Lastly, for something fun, I was at Marshall Wharf Brewing in Belfast last week when there was a commotion on the dock outside. It was a family of otters. Pretty cool to see them bound across the dock and back into the water on the other side:

Got news tips or story ideas? Email me at bsprague1@gmail.com. Have a great week, everybody.

It feels like the biggest spot you could improve things would be legalizing row houses, and either increasing the percentage of a lot that can be filled with home or just eliminating the rule entirely. When you consider that most of these inner suburban houses are using less then half the space they occupy, you could really ramp up available housing just by fitting in more homes.

On a separate note, have you looked into/seen any research on what happens to the value of condos over time? Unlike with any sort of housing where you own the land, a condo is a pure play on the availability of housing, so an increase in supply should tank their price, not to mention the downside risk of the unit degrading. Like people treat homes as non-degrading assets, largely because they are conflating the land and the building, but they then take that mindset and apply it to condos, where you just have the degrading asset. I'd be curious how those "investments" have held up.

I have trouble wrapping my mind around the demographics that can feasibly support a tiny home lifestyle (<400sf). I have to assume only a small fraction could go this route, but maybe my thinking is too limited on this. Do banks ever see clientele interested in financing a TH?

Good discussion of zoning regs and rising home prices (for latter, thanks for adjusting for inflation). No mention of land prices though - a topic worthy of a future post, perhaps. Would be interesting to see data on how the dearth of developable land materialize as home cost increases in (i.e.) Bangor, Portland and LA.