Is It Still a Good Time to Invest in Rental Properties?

Or: Rental Market Preview 2026

I would be surprised if there are many lenders in the Northeast who booked more rental property loans than I did from 2017-2023. It helped that I work for a bank that was particularly aggressive on these types of loans during that time period, but my bank also did them particularly well, with an ease of doing business that made us an attractive partner for real estate investors. We are still a great partner to our borrowers, in my opinion, and we are a fantastic bank. The landscape on rental property financing has changed quite a bit, though, over the past two years.

Rental property loan requests do still come across my desk. But the velocity of these inquiries has lessened dramatically. There was a time when I might have been working on 30+ active rental property deals at once. At any given point these days, on the other hand, I might have one or two rental property deals in the active pipeline and a handful of ongoing conversations with some of my regular borrowers about irons they may or may not have in the fire for later in the year.

Why the change? To answer this question, you have to understand that the 2017-2023 timeframe (and, indeed, the 5-10 years that preceded it), was a once-in-a-generation, perfect storm of variables to the good for the real estate investor that made purchasing or constructing rental properties extremely attractive. Consider the following:

Rates: real estate investors were generally borrowing in the 4.0-5.0% range (especially from 2020-2023), and occasionally even in the 3’s. Money was historically cheap for commercial borrowing.

Prices: much like single-family homes, rental properties have appreciated in value considerably over the past 7-8 years. But there was a time when prices were lower, and those investors that got in before the surge have benefitted from both rent growth and organic property value appreciation. This is purely anecdotal to my own market in Bangor, Maine, but when I started working as a commercial lender in 2015, I feel like the average per unit price of a rental property was about $40,000-$50,000 (yes, I know, low by national standards and by the standards of today). That would make a typical four-unit property cost approximately $160,000-$200,000. Today the per unit cost for a standard rental property in my area of Maine is around $120,000 per unit, making the average four-unit property go for around $480,000. The actual price of a property, of course, depends on many variables including condition, location, amenities, etc., but these are generally the averages for what I have seen over the past decade. It is a lot harder to cash-flow a property you bought for $480,000 as compared to one you bought for $200,000.

Inflation (or lack thereof): the 2010s was generally a period of low inflation. The annual CPI inflation rate typically ranged from 1.5-2.5% for the entire decade. Inflation started popping in 2022 and was particularly painful to people in 2023 before easing its way down to a more moderate (although frustratingly sticky) level today. Why inflation is relevant to the real estate investor is that it impacts virtually all of the expenses involved in owning a property. Insurance, property taxes, the cost of repairs, utilities — it was all comparably less expensive a few years ago, sometimes notably so, as compared to today.

Put these variables together — a low cost of borrowing, organic market growth, and a lower inflationary environment (prior to 2023), and you have a great formula for the investor.

Looking Back at Supply and Demand

Last week, in writing about the housing market, in which I was focusing primarily on single-family homes for individual and family use, I talked about how supply and demand are still the basic drivers for prices on something even as complex as a home. The same holds true in the rental market.

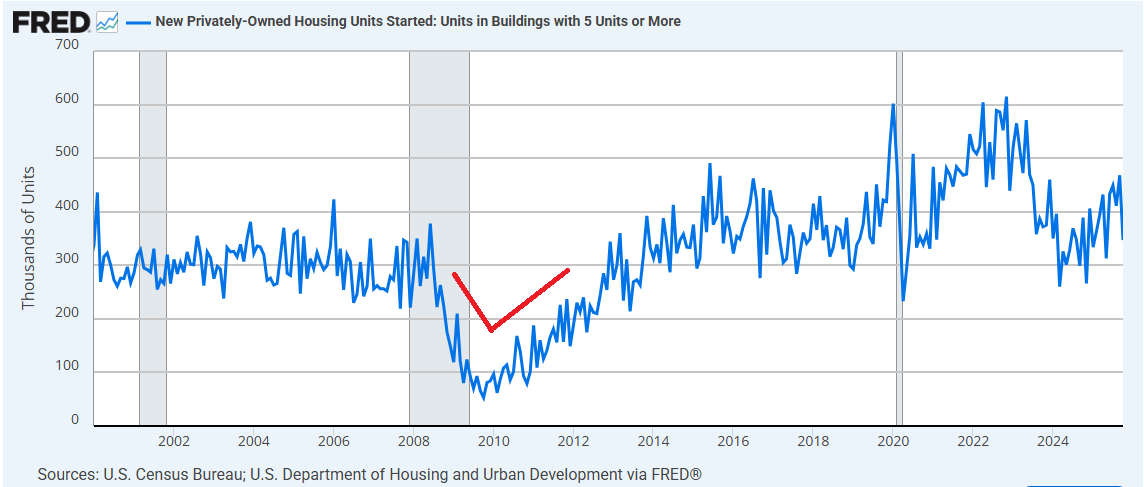

In that 2017-2023 timeframe, the supply and demand forces were both strongly tipping the market in favor of rental property owners and investors, to the detriment of tenants. On the supply side, there was a nationwide period of underbuilding from 2009-2015 in the aftermath of the Great Recession. The chart below shows the average rate of multifamily home construction (i.e. rental properties with 5+ units) going back 25 years. The red line indicates the trough of construction in the early part of the last decade:

The country was not building at a particularly robust rate leading into the 2008 Financial Crisis to begin with, but the multi-year drop-off significantly constricted the supply of new rental units, the ripples of which were felt several years later. By the end of the 2010s, the rental market was lacking several million units that were meant to have been built, but weren’t. By the way, the chart above is for construction of properties with five or more units; the chart for construction of rental properties with 1-4 units looks similar and the stories are essentially the same.

There were other restrictions on supply, too. For example, 2017-2023 also saw the rise of Airbnb and the more ubiquitous use of short-term and vacation-rentals as consumers caught on to this type of overnight stay, and property owners got keen to the cash flow opportunities. Properties that might have been rental properties (or single-family homes, for that matter), were converted to short-term rentals instead, thereby contracting the supply of long-term rental units. This was particularly common in communities with a large amount of tourism, where numerous properties have been converted from long-term to short-term use in recent years.

The Supply-Demand Mismatch

The main reason why rents rose so significantly from 2017-2023 was that the limited supply was overrun with roaring demand.

Where did this demand come from? For starters, the economy was reasonably strong during this period (acute and lasting pressures of the pandemic, aside). Unemployment was low, and when people are working, they are more likely to have money to spend including on the necessities of life, such as rent. Inflation hadn’t taken hold yet, so price pressures were generally manageable.

Second, a cultural shift has taken place where renting among older and more affluent people has become more commonplace. People don’t want to be anchored to one spot, especially in retirement. Many others simply do not want to have to care for their own property, so they are renting instead. Older people with more assets entering the rental market helped pulled rents higher as landlords and property owners realized they could charge more.

It may feel trite to talk about the influence of affluent renters on the market when so many renters are living close to the line, but I believe the influx of non-traditional renters into the pool of those seeking apartments, single-family rentals, and other types of leased accommodations is a key reason why prices have risen. I also think many property owners simply realized they could charge more and more on rents. Once the overall economy found itself in an inflationary mood, I think a lot of real estate investors realized they could price higher and the demand would still be there, so they simply started raising rents.

Lastly, I think many people also wanted to live alone or with fewer people during the pandemic, which separated out the tenant pool into more and more households, which was a catalyst for increased demand, as well.

So What About Today?

Let’s look at each one of these variables for a look at what the landscape looks like today.

Rates: the interest rate environment is not nearly as attractive for borrowers as it was a few years ago. The picture has eased in a slightly better direction over the past 6-12 months with some interest rate reductions by the Fed, but still, the cost of borrowing was around 4.5% five years ago; today it is around 7.5% (give or take), and sometimes higher depending on the source of financing (I still see hard-money and national non-recourse lenders putting money out there for 10-12+%).

Prices: I mentioned above how per unit costs (and, therefore, the total cost of the property) have risen dramatically over the past few years. That is good news for those with a current portfolio of properties, but bad news for those who are trying to get into the market. It’s just harder to cash-flow an investment when your starting cost is $450,000 than when it was $200,000, as noted above. I fear for some of the younger investors who are just getting started out today, who may be chasing a playbook that worked better with lower acquisition costs (and lower rates), and is not as viable today.

Inflation: price increases have decelerated a bit, but prices certainly have not fallen in any sort of meaningful way. Take insurance, for example. According to a Federal Reserve research paper from this past September, “The average monthly cost [for multifamily property insurance] increased from $39 per unit in 2019 to $68 per unit in 2024 in real terms, an increase of more than 75 percent.” Interestingly, the Fed researchers report in their analysis that the majority of this increase is simply eaten by the property owner, while only a portion is able to be passed along to the tenant. Although the average monthly premium has increased by $29/month, the Fed finds evidence that only $7-$12/month of this is passed along to the tenant; the remaining amount just erodes the property owner’s margins. The same is probably true for property taxes, which are rising virtually everywhere, and other expenses like repairs.

One key point to reiterate about inflation: real estate investors benefit from inflation only when rents rise faster than costs. That relationship has broken down over the past four years, though. Costs have risen faster than rents, which has tightened the margins or, for some, even eliminated margins altogether. And as much as real estate investors believe they can pass along the higher costs to their tenants, they can really only pass along what the market will bear.

What About Supply and Demand Today?

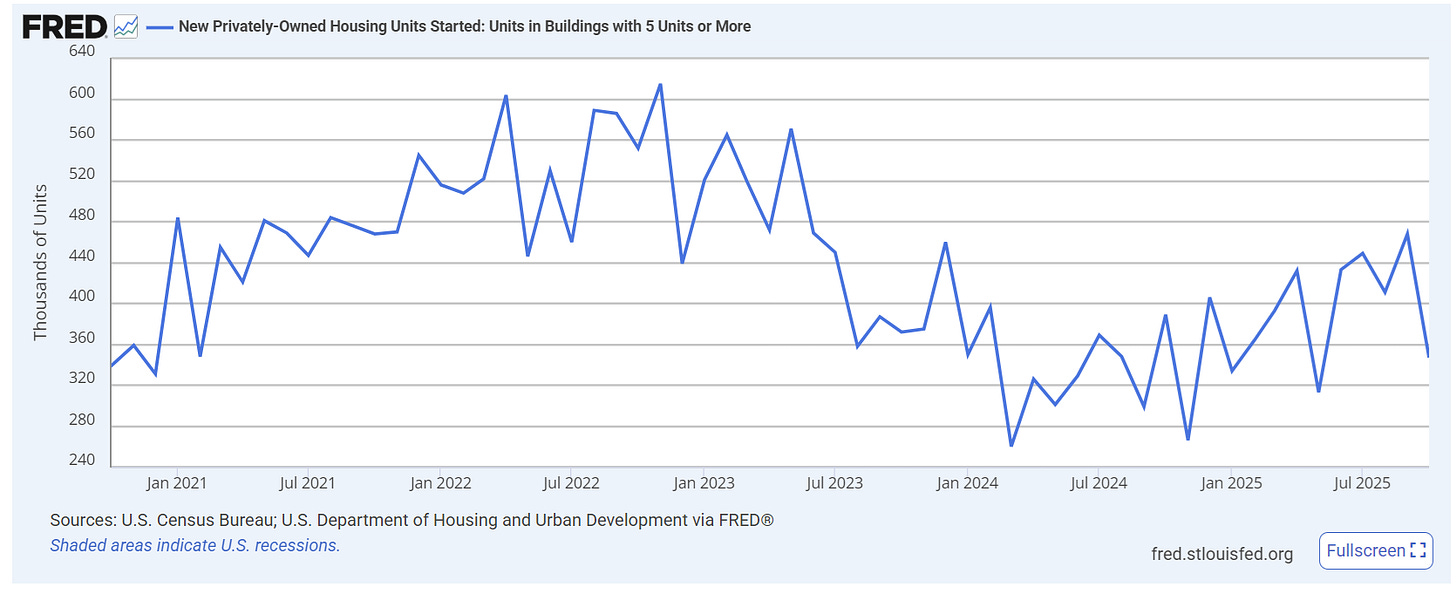

On the supply side, construction of new rental units has actually eased down a bit over the past two years. The chart below illustrates the decline since 2023, which I believe is largely a function of increased interest rates (which mean higher costs to the builder who is financing their construction projects) not to mention other increasing costs like permitting, engineering, and, of course, building materials and labor. At the recent peak in October 2023, the country was building at a pace of 600,000 new units/year. In October 2025? A rate of just 347,000 new units/year.

Still, there were many new units that did come online from 2020-2025. Keep in mind the chart above is for housing starts, and not completions. A unit that was started in 2023 may not actually have hit the market until 2024 or even 2025 depending on the length of the construction process. The impact of the supply surge that did happen is playing out now, with the result being a deceleration of rising rents and even rent decreases in certain markets (more discussion on this below) as tenants have more choices and property owners must price units in order to attract tenants.

On the demand side for rental units, unemployment remains fairly low, although as has been a general theme in The Sunday Morning Post over the past year, the view on the economy depends a lot on where you sit. Many people are struggling with high costs at the grocery store, with utilities, and yes, with high rents. The general uncertainty and economic malaise that many people are experiencing (not to mention outright frustration and anger) has a lot of people frozen in place and wondering how they are going to get by. I talk to a lot of landlords and property owners weekly (granted, mostly only in my local market), and the general sentiment is that in this climate, they are keeping rents flat. There is certainly not a frenzy of raising rents to the upside. Again, the market will just not bear it.

Where Are Rents Going Nationwide?

There are several different aggregators of rental data with different methodologies that all show generally the same thing: nationwide rents are moving sideways and are even starting to decline, particularly in certain markets. The Zumper Rent Report has shown flat rents for five straight months through November. The greatest rent increases were in San Francisco (+15.9%) year-over-year, while rents are down in the Southwest (e.g. down 7-10% in Phoenix and Glendale). Rents are down in the D.C. area. Per the report:

D.C. rent slid sharply in November, pushing the city out of the top 10 rankings, as one-bedroom rent fell 5.7% year-over-year, one of the steepest declines among major coastal markets. The city had already been modestly cooling following the DOGE cutbacks, and the recent government shutdown added another headwind to a supply-demand dynamic that was already weakening earlier in the year. Neighboring Arlington wasn’t immune either, with one-bedroom rent down 2.1% annually, reflecting broader downward pressure across the D.C. metro area.

Flat rents in an environment where inflation over the past year was close to 3.0% actually means that comparatively speaking, rents are down. As incomes increase relative to flattening rents, affordability will improve.

The Apartment List Rent Report for January 2026 found similar data. Per Apartment List:

Rent prices nationally are down 1.3% compared to one year ago. Year-over-year rent growth has been slightly negative for more than two full years, and the national median rent has now fallen from its 2022 peak by a total of 5.9%.

This data generally matches other sources, as well, which all show flat rents nationwide, and falling rents in areas that generally had the most construction of new units over the past few years.

One of those areas is Austin, Texas. I wrote about Austin almost two years ago as an example of a community where rents are falling the most, which uncoincidentally corresponded with a massive construction boom in the creation of new rental units. At the time of that writing in March 2024, there were nearly 50,000 new rental units under construction in the Austin metro area, which represented a massive influx of new supply.

I spoke to real estate investor David Pio this week to talk more about Austin. David is based on the midcoast of Maine, but has experience investing in Austin. He told me:

Austin rents were some of the highest in the country going into 2022. At the same time Austin had some of the most permissible zoning and virtually nothing governing the addition of new supply through development. The development story was further supported by the influx of new residents to Austin and Texas for a variety of reasons during and after the pandemic. With companies moving to the area, new jobs were being created and new housing was needed. As is usually the case with development, especially in boom-and-bust markets like Texas, the market got overbuilt. What was at first the darling of the investment world, Austin is now performing the worst. Rents across the board are down anywhere between 15-20% and current occupancies are hovering between 80-85%.

Indeed, rents in Austin are falling dramatically, and are doing so faster than virtually anywhere else in the country. David Pio added in a comment to me, “From the perspective of Maine (or anywhere else for that matter) wanting to lower housing costs and rents, the best way to do that is by adding supply and a lot of it.”

It Is Still a Good Time to Invest in Rental Properties?

So, this rental market preview for 2026 article turned more into a rental recap of the past few years, but the question still needs to be answered: is it a good time to invest in rental properties. It depends a lot on the market you’re in, the price you can acquire a property for, and the rents you can achieve. This may sound obvious, but it is the case that each investment opportunity is going to be different. Investors should not plan to achieve year-over-year rent growth of 5%, which is what I see on a lot of models and pro formas that come across my desk. Your model has to work if rents are flat and, indeed, even if they fall and while other expenses rise. Investors should be particularly cautious to buy in a market where that has been a lot of new construction in recent years, or a lot of new units permitted to be built in the year ahead. That being said, although certain markets like Austin are now overbuilt at the moment, the rate of construction of new units nationwide has actually declined over the past two years, as noted in one of the charts above.

On the construction side, I think virtually the only people who are having cash-flow success in the construction of new rental units right now are people who are either doing much of the work themselves, which allows them to save on some of the costs, or who have found subsidies through government programs or local and state housing initiatives. There should be more support for housing construction in this way, which is a topic that I will try to take on in a future article. After all, the challenging thing for the rental market over the next few years is that, at least from the tenant’s perspective, if we want to see rents continue to become more affordable, you need a much more robust rate of construction. But as noted above, construction is slowing down rather than ramping up. So this may be a place where government needs to step in to support further development.

Summing up the 2026 rental market preview discussion: I see rents staying basically flat this year in aggregate nationwide, and that rents will continue to fall in places that have seen the most construction over the past several years. A softening labor market could put a wet blanket over any potential rent increases, as the market might just not bear any sort of meaningful rise from where we are now on rents. Some of this is on a pendulum, though, and all of these variables are connected. With home prices for purchase remaining high and mortgage rates still a bit elevated, it may keep more people in the renter pool for longer, especially as rents drop relative to overall inflation. This might boost rents back up. That said, the top overarching variable is the health of the economy, and that is a topic that is both tied to everything I write about here, and too complicated for any one single topic.

Addendum - Alternative Yields

One factor I believe has been underappreciated in the big rise in rental property investing in 2010-2023 timeframe is that investing in real estate became a viable and sought-after alternative investment strategy to more traditional routes like putting money into stocks, bonds, and certainly savings and money market accounts. The stock market had a very good decade-plus, that’s for sure. But yields on traditionally safer investments like bonds and bank accounts were next-to-nothing for over ten years. You could literally not get pennies on the dollar on a money market account for many years. That is one reason, I believe, that so many investment dollars flowed into real estate — people were chasing yield. Real estate filled the yield vacuum.

Today, that vacuum no longer exists. You can earn decent returns in a money market account with daily liquidity, absolute safety, and no tenants to manage (although, to be fair, money market rates have generally declined over the past six month as interest rates have come down). But Treasuries offer comparable yields, and don’t require responding to any maintenance calls at midnight. Even investment-grade bonds now provide income that investors would have drooled over in that 2010-2023 range.

Pension funds, insurance companies, endowments, and family offices all chase yield, and what they particularly like is non-correlated returns from the stock market as it makes for a more well-diversified and safer portfolio. There are trillions of investment dollars out there chasing yields — much of it flowed into real estate, which drove up prices — but who knows where it will go now that returns on real estate are more moderate and yields in other areas are higher. When that amount of money starts flowing, it is bound to have an effect on prices and returns, though.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com. Thoughts and opinions here do not represent First National Bank.

The CPI is perhaps sticky as states raise their minimum wage. Maine’s just went up 3.8% January 1, 2026, from $14.55 to 15.10.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_U.S._states_by_minimum_wage