It's Still Expensive to Build

Plus: a bifurcated building market

If you’ve tried to put an addition on your house, build a deck, or even just replace a fence or some windows in the past few years, you know the story: materials and labor cost more than they used to (and sometimes a lot more). What began as a pandemic-era spike in lumber has rippled across nearly every corner of the construction world. While prices have eased in some areas, the overall cost of building remains high thanks to increases elsewhere.

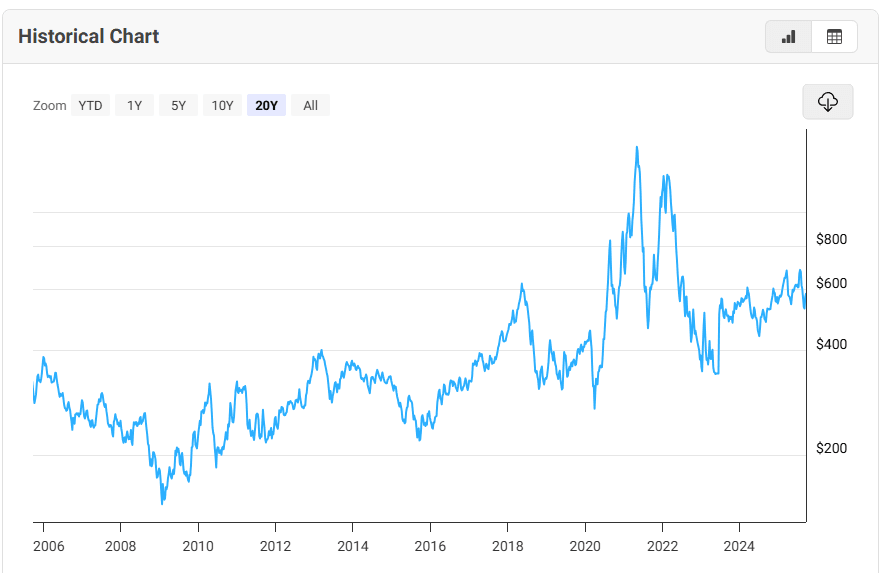

There are some bits of good news. Lumber, which was the headline villain of 2021 when a two-by-four felt as precious as a gold, has continued to come down. The chart below shows the average price per thousand board feet, which as of last week was about $583, down about 15% since July, and down quite considerably from the pandemic highs — the price briefly spiked to over $1,600 in May 2021!

For a builder framing a house today not to mention the eventual homeowner, that relief is real. (As a very quick aside, I wrote about lumber prices coming down from their May 2021 prices in one of the earliest Sunday Morning Post articles I ever published. Somehow my actual article ended up on Drudge Report, and was read over 50,000 times in the span of about three hours, which was a surreal experience, for sure).

But back to the lecture at hand: the lumber reprieve has limits. Metals tell a different story. Copper pipes are up over 40% this year, and wiring has climbed double digits. Steel and aluminum remain stubbornly high, with iron and steel products up more than 9% year-over-year and copper wire and cable nearly 14% higher. Tariffs add fuel to the fire, including on the lumber front. The U.S. recently doubled down on duties for Canadian softwood lumber, bringing the total tariff rate to 35%. That means even as wood markets soften, tariff policies may prevent prices from falling as much as they otherwise would.

The broader basket of building materials reflects this uneven tug-of-war. According to industry data, input prices rose 0.2% in August, and year-over-year inflation in building materials has ticked back above 3%. That doesn’t sound like much in isolation, but after years of volatility, even small upticks matter. The 3% increase also outpaces overall inflation in the economy. The lack of meaningful price declines reinforces the sense that “cheap” building materials are not coming back anytime soon. On top of this, labor costs have also continued to rise at basically a robustly steady pace for the entire past decade.

Even though things aren’t as volatile as they were from 2020–2022, some of the contractors I speak to regularly still report that quoting a job today can feel like trying to hit a moving target. When prices fluctuate as much as they do, it’s safer for contractors to price things high, but it also means that some homeowners and businesses will simply wait. Which brings me to the second part of today’s topic.

Bifurcated Market

There was an interesting tidbit in the latest University of Michigan report on consumer sentiment:

Consumer sentiment confirmed its early-month reading and eased about 5% from last month but remains above the low readings seen in April and May of this year. Although September’s decline was relatively modest, it was still seen across a broad swath of the population, across groups by age, income, and education, and all five index components. A key exception: sentiment for consumers with larger stock holdings held steady in September, while for those with smaller or no holdings, sentiment decreased.

In other words, those with investments in the stock market are feeling better about the economy than those without (or, more accurately, they feel less bad). And why wouldn’t they? After a fairly significant drop in the stock market this spring, stocks have not only recouped those losses but are now up about 13% for the year (the tech-heavy NASDAQ is up close to 17%). This follows a 25% gain in 2024 and a 26% gain in 2023. At those figures, a $1 million stock portfolio that is keeping up with the benchmark would have grown by over $500,000 in just two years, and nearly another $200,000 so far this year.

Stocks have dropped only twice in the last sixteen years. This steady wealth accumulation among households with significant investment portfolios is fueling investment in other areas, such as home improvements. That represents demand-based inflation: prices are rising because enough consumers have disposable resources to keep spending, because they are achieving such gains in the rising value of their assets. This includes rising real estate values, too, along with increases in stock accounts (including retirement accounts).

What I see is a bifurcated market. Those with existing resources are pulling further ahead, and their spending habits are driving demand-based inflation. Those without investable assets—or who are just starting out—have more limited options, yet still live in the same economic ecosystem shaped by these price pressures, which creates powerful dynamics of the haves vs. the have-nots.

You can see the same pattern outside construction. Hotels and restaurants, for example, are comfortably charging $600 a night or $250 for a fine-dining meal because there are enough customers able and willing to pay. Businesses naturally cater to this demand, but the result is a market that feels very different depending on which side of the wealth divide you’re on.

Conclusion

The story of construction costs today is really a story about the broader economy. Lumber has eased, but metals, tariffs, and broader inflationary forces keep overall costs high. At the same time, the stock market’s extraordinary run (matching a similar run-up in real estate values) has bolstered a subset of households with the means to keep spending, even as many others pull back.

That tension between easing in some corners and stubbornly high costs in others, between households with significant assets and those without—defines the current moment. It explains why some homeowners are eagerly upgrading kitchens and adding additions while others are postponing basic repairs. It explains why luxury hotels and upper-end restaurants are booked solid even as grocery shoppers complain about prices.

In short, we’re living in a bifurcated economy. And for anyone trying to build, whether it’s a house, a business, or just a financial footing, the path forward depends a lot on where you are starting out. While it is true that many who do not have as much now often have the luxury of time to grow and accumulate more, taking advantage of the power of compounding along the way, the divide at the moment is real, and is likely one of the reasons behind the economic angst so many feel, not to mention a source of political unrest, now and in the future.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.