Just Give It Away?

When and why companies give the product away. Plus: the Coca-Cola Santa Claus.

Sometimes a business has a unique problem, however, in that its target customer base simply does not exist. This could be because no one actually wants to buy what the business is selling. But there is another reason a customer base might not exist: because the product is so new, or so innovative, that people do not yet understand it or do not know that they want or need it. What a business must do in this scenario is actually create the audience for its product so that audience can then buy it. This comes through education, aggressive marketing, and a strategy that plays the long game instead of relying on short-term windfalls, a difficult strategy, for sure, especially for under-resourced startups without a long time horizon.

The best modern example I can think of in this realm is the iPhone. Steve Jobs basically stood on the stage at a major Apple announcement event and told the world forget everything you know about your phone. Rather than compete on the existing plane against the Blackberry’s and Nokia’s of the world, Apple created an entirely new field of play and, with it, an entirely new market audience.

Before 2007, people had a fixed idea of what a phone was: physical keyboards, carrier-controlled software, and a limited, frustrating version of the internet. Apple challenged those assumptions all at once. A phone with no keyboard seemed like it had a missing piece, touchscreens felt impractical, and the idea of real web browsing on a phone was almost laughable. Rather than argue, however, Apple taught through experience, which included live demos through traditional media outlets and friendly, patient, dynamic in-store experts who could educate people in millions of one-on-one interactions. Apple Stores became the hottest spots in the mall, often overflowing with customers eager to get in on the product. Seriously, I remember an investor friend telling me they started buying Apple stock in 2011 “because the Apple Store in the Maine Mall was the only place with a line.” Not a bad strategy at all.

By collapsing a phone, an iPod, and an internet communicator into a single object, Apple used familiar ideas to introduce new consumer behavior. The “phone” became a device much more expansive than just a phone. In fact, I think for most people today, the traditional dial-and-receive-calls functionality of a smartphone is one of their lesser used apps, and all because Steve Jobs told the world to forget what you know about a phone.

Apple didn’t give the iPhone away for free, but it reduced financial risk through carrier subsidies, bundled software, free updates, and a mostly free App Store. By the time competitors caught up technically, Apple already owned the model, and the market followed.

You’ve Got Mail

One of the most successful marketing campaigns of all-time was for a company that, ironically, barely exists today: America Online. While some people still have “@AOL.com” email addresses, the iconic and nostalgic screech of a modem connecting through a phone line is no more. In fact, AOL only recently discontinued this system of dial-up internet access in September 2025. But for many Americans of a certain age (including an elder Millennial such as myself), America Online was a critically important and impactful company.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, AOL dominated the home internet market, with the company providing internet to over 20 million Americans. The story of AOL’s fading way is an interesting one, but beyond the scope of today’s article. In short, competition and technological advancements caught up with AOL. Their product moat evaporated. AOL also attempted a misguided acquisition of Time Warner in 2001, which precipitated a steady decline. AOL was eventually acquired by Verizon, merged with Yahoo, sold to Apollo Global Management, and then just recently sold again to an Italian firm named Bending Spoons, which has collected several U.S. technology brands including Vimeo, MileIQ, Meetup, WeTransfer, Eventbrite, and now AOL.

But back to the glory days: when America Online was attempting to grow market share in the mid 1990s, they had one notable problem, which is that no one knew what the internet was. In this now-iconic (and truly historical) clip from The Today Show in 1994, a confused Bryant Gumbel asks, “What is the internet, anyway?” amid a meandering conversation with Katie Couric and Elizabeth Vargas about what the “@” sign means and how do you read it. They are legitimately confused (the one minute, 26-second clip is worth a watch…you can view it here).

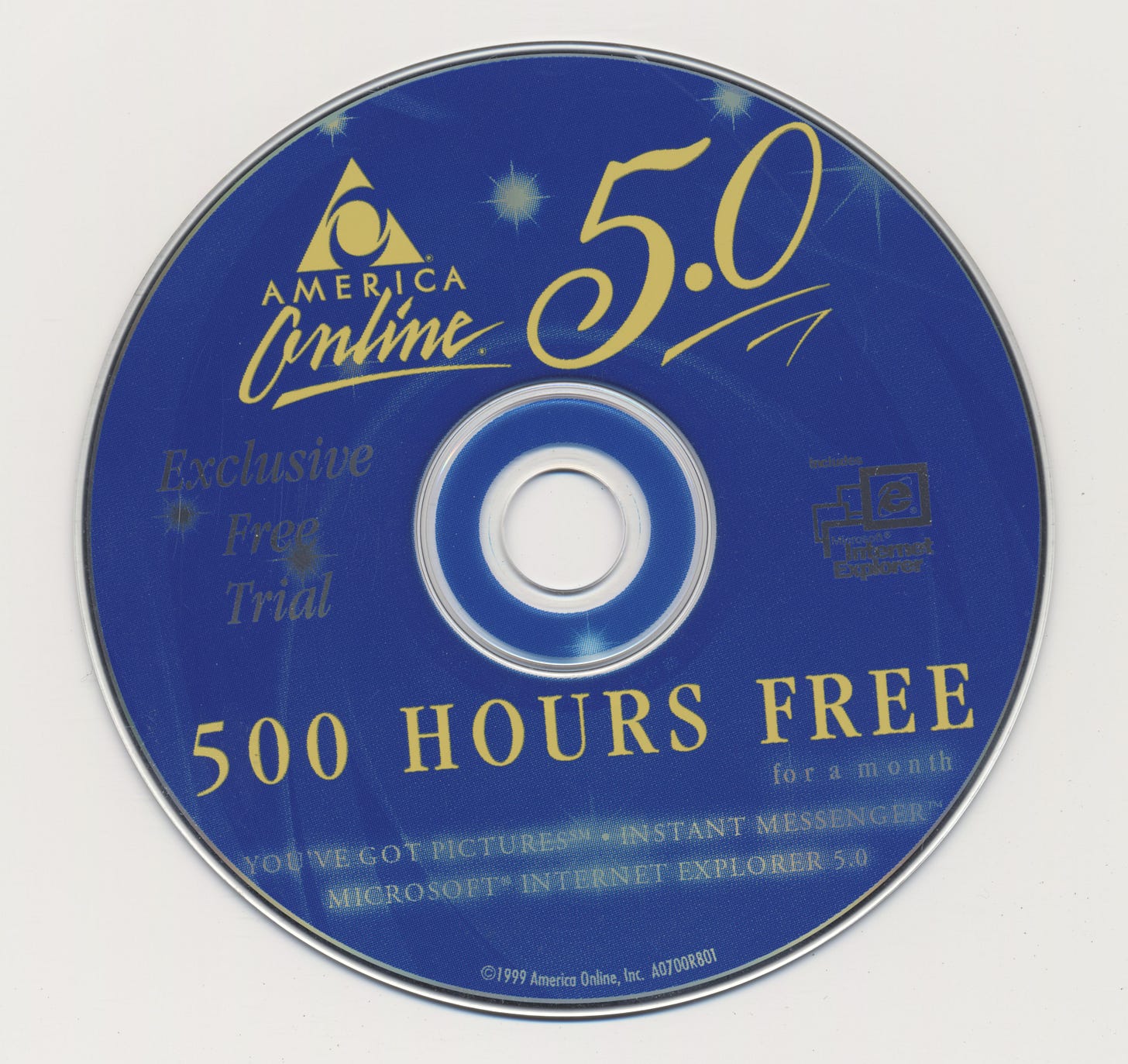

So how did America Online approach an American public that had no idea what the internet was? Anwer: they gave it away. There was a period of time in the mid to late 1990s when you could get a free CD with America Online on it at the grocery store, bookstore, record store (another 1990’s relic), and other similar spots. The CDs were sometimes included in a pocket sleeve of magazines, and often simply mailed to people unprompted or distributed as part of some promotional giveaway. The costs to create the CDs were minimal, and the America Online business model relied on fast customer growth. With an American public that felt much like Bryant Gumbel and Katie Couric with regard to what is the internet, AOL had to literally give itself away to build its market base. Now, keep in mind those CDs came with 50, 100, 500 free hours and then people would have to pay, but the free CD campaign remains, to this day, one of the most successful marketing campaigns of all time. America Online became the dominant player in the home internet and email market, albeit only for a few years before others caught up and surpassed the technological and cultural icon, as noted above.

Buy the World a Coke

The Coca-Cola company is 139 years old, which makes it one of the oldest continually operating brands in the world. But imagine, if you will, a time before Coke. Not only was there no Coca-Cola Classic, there were no cola soft drinks at all. In fact, Coca-Cola created the “cola” descriptor, which taken from one of the ingredients, kola leaves (the early Coca-Cola recipe also has trace amounts of cocaine in it; yes, this is actually true).

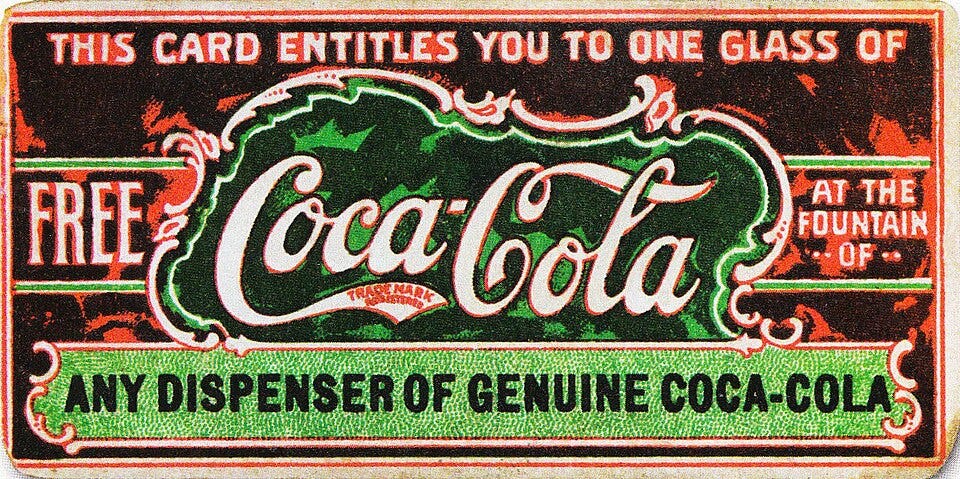

In 1887, there were root beers, ginger ales, and fizzy tonic waters, but nothing with the distinctive flavor, taste, and sensation of a Coke. So in order to get Americans to try it, Coke did the same thing America Online would roll out over 100 years later: they gave it away. Hundreds of thousands if not millions of coupons for free Cokes went out in publications around Atlanta, which is where the Coca-Cola company was started, and then throughout the southeast, and then eventually around the country. The “Free Coke” campaign lasted decades and converted countless Americans to the new cola soft drink. In fact, the image at the outset of today’s article is believed to be a scan of the very first Coke coupon, which was not only the first coupon in the Coke campaign, but thought to be the first print coupon created…anywhere!

What It All Means

At first glance, these stories may seem disconnected—one about smartphones, one about dial-up internet, and one about soda. But they all point to the same underlying truth: when you are selling something fundamentally new, you are not just selling a product, you are selling an idea, a behavior, and often an entirely new way of thinking.

In markets like these, immediate monetization is often the wrong goal. The real challenge is adoption. People can’t buy what they don’t understand, and they won’t pay for something they don’t yet trust or value. Apple, AOL, and Coca-Cola each recognized this and made a deliberate choice to lower friction at the point of entry, whether through free trials, subsidies, or outright giveaways, in order to educate the market and build habits, preferences, and, particularly in the cases of Apple and Coca-Cola, brand loyalty.

If you look at the most successful tech companies to emerge from the 1990s and early 2000s, the ones that endured were rarely the ones that monetized first. In fact, the opposite was often true. Companies like AOL, GeoCities, and the canonical dot-com cautionary tale Pets.com pushed aggressively toward revenue before fully establishing value. Meanwhile, companies like Google, Amazon, eBay, Facebook, and Instagram focused first on scale, usability, and trust, sometimes without even knowing exactly how they would monetize until years later. Yet these were the ones that became the most profitable and the most valuable.

The problem, of course, is that most new businesses don’t have the luxury of infinite runway. Giving something away for free is expensive, risky, and often terrifying. But the lesson here isn’t that every startup should give its product away indefinitely, it’s that value creation must precede value capture. If your audience doesn’t yet exist, your first job isn’t to extract revenue from it, but to bring it into existence.

Addendum

I was planning to write an article about this “Just Give It Away” strategy at some point, but the extra catalyst this week was listening to the most recent episode of what has become my favorite podcast: Acquired. In this ongoing series, the co-hosts do multi-hour deep dives on the founding stories of various companies. They focus a lot on tech companies, which are certainly interesting (e.g. Amazon, Google, NVIDIA, etc.), but they also cover some other types of retailers and non-techy companies, including the feature of their most recent episode: Coca-Cola. It is worth a listen. Find it here or wherever you listen to your podcasts. I learned a lot.

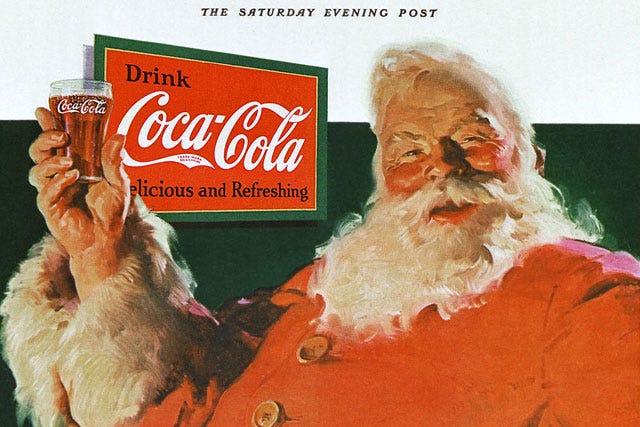

Anyway, in terms of marketing, Coca-Cola is certainly a heavyweight. They are perhaps the most influential marketing firm in corporate history, with campaigns like the Christmas polar bears, the “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” campaign of the 1970s,” the Always Coca-Cola branding of the 1990s (I can still hear the short jingle in my head), and, of course, the company’s association with Santa Claus.

The Coca-Cola company didn’t invent the concept of Santa Claus, but they did create our modern understanding of the plump, jolly, warm, red-and-white-clad Santa Claus that we hold dear today. This began in 1931 when Coke commissioned an ad design of Santa Claus drinking a Coke by artist Haddon Sundblom, which helped to quickly associated the drink with the holidays. As I learned in the Acquired podcast, one of the primary motivations for the campaign was to get people to drink Coke in the winter, as previously it was thought of mostly as a refreshing summertime drink. After the Santa Claus campaign took hold, which ran seasonally for decades, Coca -Cola’s internal numbers showed that more Coke was consumed during December than in any other month. I guess you could say the campaign was a success.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Have a great week, everybody, and more importantly, a very Merry Christmas and Happy Holidays. Happy Hannukah to our Jewish friends, and Happy New Year to all (I’ll still be back with one more article in 2025 before we turn the page to 2026. See you next week for that!). In the meantime, Merry Christmas from my family to yours.

LOL - I remember getting so many AOL CDs in the early 2000s that we were hanging them from our fruit trees to deter the crows. Very interesting to look back at those times through the perspective of this article...

Merry Christmas, Ben! Thanks for reminding me with a video image that my understanding of the internet is about as deep now as was the conversation on Today 21 years ago...