Multiunit Construction is Plummeting

A look at the data and math at play

At a press conference in January, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell lamented the high cost of housing, but said that it was not the Federal Reserve’s job to rein it in. “We’re not targeting housing price inflation, the cost of housing, or any of those things. Those are very important things for people’s lives. But they’re not—you know, those are not the things we’re targeting.”

Why not? Because the Fed has a dual mandate: price stability and stable employment. Expensive homes and unaffordable rents may be societal woes, but don’t ask the Fed to solve them because they have neither the tools nor the mandate to do so, Powell is saying.

The Fed Chair did offer a thought or two about why housing prices have become so high, saying, “You know, we have a built-up set of cities, and, you know, people are moving further and further out. So there’s—there hasn’t been enough housing built.” In other words, it is a question of supply. Build more housing and both home prices and rents will come down, Powell is implying, but the policy tools to incentivize or otherwise boost that supply rest in other areas of government, including Congress and perhaps state legislatures and even municipal town and city halls - not with the Federal Reserve.

And yet, the Fed’s policies on interest rates do drive the levers of both supply and demand for homes and rental units. When rates were brought low for an extended period during the pandemic, demand for homes surged, which led to major price increases. Sure, there were plenty of other variables at play including COVID-related movements of people around the country, inward-looking behavior in the midst of, let’s face it, a weird period of time, and diverted spending from entertainment and travel into homes and rents. But low interest rates were the driving variable, a function of Fed policy.

The Multiunit Data

Now that the Fed has raised interest rates back up, it is hitting a different part of the housing continuum: construction of new units. The number of new multiunit rental properties that have been initiated around the country has fallen off a cliff in the past year. Just one year ago in May 2023, there were approximately 575,000 new units started on a seasonally-adjusted basis. In May 2024? Just 278,000, which makes for a drop of over 50%. The current number is near ten-year lows barely seen since the trough of the Great Recession.

Why the drop off? It’s all about the math. Projects just do not cash flow as well in the current environment. Part of that is the high cost of building materials and the limited labor supply, which makes for its own high costs. Another variable at play is the rising costs of things like insurance and property taxes. Much as people’s daily expenses have gone up significantly in the past two or three years, so too has the cost of both building and maintaining a property.

But the big variable is interest rates. The math just doesn't work when the interest rate on a project or acquisition begins with a 7, 8, or 9, as it typically does these days, whereas three or four years ago it would have started with a 3, 4, or 5.

Consider the following example. These are very back of the envelope calculations, but when reviewing the cash flow on a prospective deal at a 30,000 foot level, I typically assume 10% vacancy on a project, which is a conservative assumption these days but it is what we use. Then I assume that 40% of the gross rents are going to be eaten up in expenses, like the aforementioned insurance and property taxes plus repairs, management fees, and utilities, etc.

Let’s say we are looking at a five-unit property being purchased or built for $600,000, which would be an average cost of $120,000/unit, which is about what I am typically seeing these days in my local market. And let’s say each of the five units generates $1,600/month in rents, so $8,000/month or $96,000/year from the overall property.

What does the rest of the math look like? First factoring in the 10% vacancy assumption brings this gross income down to $86,400. Then applying the 40% expense ratio, it brings the income-after-expenses number down to $51,840. That might sound like great income on a property for a year, but unless you paid cash for the property, there is another big expense at play that is not factored into the 40% expense ratio yet: the loan payments.

On a $600,000 purchase or new build, the bank might finance 75%, which would make for a loan amount of $450,000. Assuming an 8.5% interest rate and a 20-year term, the monthly payment on that would be about $3,905/month or $46,848/year. This amount would have to be subtracted out from the above profit number to show the true net. Net income of $51,840 and then a loan payment of $46,848/year still makes for a marginal net profit at the end of the year, but not by much.

I’m definitely oversimplifying things a great deal here. Maybe rents are higher or the interest rate is lower. The value of the property could appreciate, which is a benefit itself, or the tax advantages could make the whole thing more viable than I’m illustrating. It’s not exactly as simple as pointing to the $5,000 in the example above and passing judgement on that alone. But you get the point. That’s still a lot of work to make $5,000 even if there may be some other benefits around the edges or over the long-term through price appreciation. If you were to put that $150,000 into a money market account earning 4% interest, you’d actually earn $6,000 risk-free, and that money, too, would compound over time.

We could look at this same hypothetical deal on paper under some assumptions about how things were in, say, 2021. At least in my local market, the same five-unit that is being sold for $600,000 today at an average of $120,000 per unit might have been sold for $90,000/unit or $450,000 in 2021 (and, honestly, it probably would have been sold for $65,000/unit or $325,000 in 2018 or 2019). Using the $450,000 purchase amount from 2021 would generate a loan amount of $450,000 x 75% = $337,500. That helps the math a lot right there - to borrow $337,500 to acquire or build a property instead of $450,000. Assuming rents of $1,500/month for each of the five units generates $7,500/month or $90,000/year of gross income. Applying the 10% vacancy ratio and then the 40% expense ratio generates $48,600 of net income in this example.

But then, you have the loan payment. Assuming a $337,500 loan at a 4.50% interest rate with a 20-year term, which is what the interest rate would have typically been back then, it generates a monthly payment of $2,135/month or $25,620/year. Taking the $48,600 of net income and reducing it by the $25,620 of annual loan payments, and you get $22,980 of net income from the property. This is a 4x multiplier over the net income from the same theoretical property today under current market conditions. And keep in mind, too, that in the 2021 example, we reduced the rents by $100/month for all five units from today’s assumption of $1,600/month to $1,500/month. The net profit in 2021 would have still been more than four times higher than it would be today. That is why these types of deals and construction projects were so ubiquitous in 2021, and why they are drying up in today’s market.

What Comes Next

I can say from where I sit, the number of rental property financing requests has really slowed down. I don’t think that will change until one of two things happen, or perhaps both: a drop in prices or a meaningful drop in interest rates. Either one of those things or the combination of the two would change the math formula and make the acquisition or construction of new rental units much more viable. The most common rental property construction projects I see getting funded right now are ones in which the developer can do the majority of the work themselves. That is the other way to make the projects work: to borrow less because you either have the cash to self-finance or you can do a good portion of the work for cheap, thereby lessening the need to finance as much.

Rents have actually eased up nationwide in the past year. We are not seeing such robust price increases in rents the way we did from 2020-2022. I plan to come back to this topic in the coming weeks. Perhaps that is another reason why these projects are slowing down, which is that the frenzied demand for rental units has eased up ever so slightly, as has the likelihood of a developer being able to consistently increase rents over time, which is another way to make the math work over the long haul.

But the housing crunch overall has certainly not gone away. It likely won’t until there is significant new construction of rental units. A lot of new units are actually coming online this year; the statistic at the outset of today’s article about new multiunit projects is about new starts and not new completions. There are actually quite a lot of new completions coming online in 2024 that were started perhaps 6-12 months ago. But once that pipeline of new units coming online slows up by virtue of their actual completion, the data on new housing starts shows a more bleak picture for the latter part of 2024 and into 2025 in terms of increasing supply. That is unfortunate news for tenants and would-be tenants who are still frustrated or unable to make ends meet from high rents.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

The Sunday Morning Post is offered free of charge. To learn how (and why) to become a paid subscriber, read here. Thank you for your support.

Weekly Round-Up

I continue to listen regularly to the Acquired podcast, which I can’t recommend enough if you are interested in the stories behind the founding of some of the most interesting and influential companies in the world. This week I listened to the Starbucks episode, which features one of the founders and the longtime CEO, Howard Shultz, telling the story of the early Starbucks years. One fun fact: if all of the money saved on Starbucks cards was considered to be in a bank, it would make Starbucks the tenth biggest bank in the country in terms of deposits.

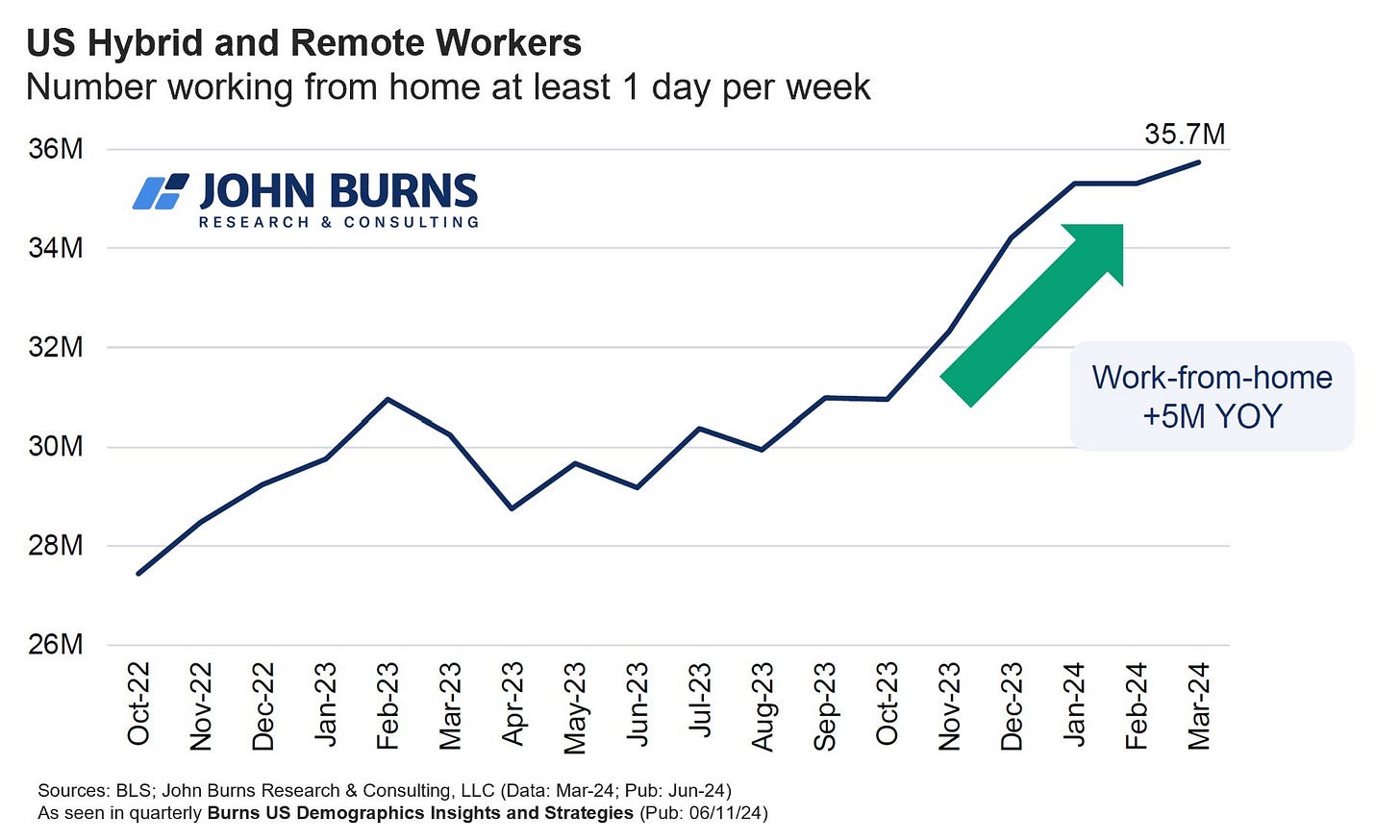

Rick Palacios Jr. of John Burns Research shared a chart showing the number of people who work remotely at least one day a week is actually still on the upswing. It has felt to me a bit like the tide had been reversing on work-from-home, but the data suggests that is not the case.

Mike Simonsen of Altos Research shared a chart on X showing the inventory of homes for sale in the Austin market is approaching 10,000 for the first time in over a decade. The inventory is coming back, people!

Have a great week, everybody!

This is a great article that should be read by every local town in Maine wondering why developers aren’t lining up to build housing with everyone wanting to move here. I could see a part 2 of this article outlining how the deal economics might change if density is allowed to increase which is a tool local governments will have to play with if we are going to see housing built in an appreciable way (not reliant on state or federal subsidies). The reality is that I don’t see interest rates going down anytime soon and property taxes have a long way to go up to cover years of deferred maintenance. Insurance will only continue to skyrocket as well. So, the two things we can do are increase density and find ways to increase availability of labor supply. These are the two critical levers to pull now.

In contrast, just 30 minutes away from Bangor, Ellsworth is having a multi-unit application and construction boom. I understand it doesn't fit the narrative of this post, and perhaps you are more interested in describing the mechanics of interest rates, however this current and future multi-unit construction is significant and notable.