New York City Hits the AirBNB Kill Switch

Welcome to The Sunday Morning Post! Thanks for reading. If you enjoy what you see here, please consider sharing with friends and colleagues.

In the face of rapidly rising rents and limited new housing supply especially in the lower and middle tiers of the housing spectrum, New York City enacted strict restrictions against AirBNB’s and other short-term rentals in January 2022. But whether it was from a lack of conviction behind said regulations, disagreement about possible enforcement mechanisms, lack of staff to actually enforce the provisions, or from simply wanting to provide existing short-term rental owners with a fair amount of time to adjust, the agreed-upon restrictions were not enforced.

That was until this week, however, when New York City started to crack down on short-term rentals in an effort that AirBNB itself has called “a de facto ban.” How did New York City and its thousands upon thousands of short-term rental operators get to this point? And what comes next? Let’s dig in.

The Lead Up

According to one report, AirBNB netted $85 million in revenue from New York City alone in 2022. It’s not surprising why short-term rentals have been so popular in a city like New York. There are a lot of mobile people moving in and out of the city on a temporary basis whether it be to work in a hospital, on a stage, at a university, or any one of countless other places people might work who are following their dreams. Plus, of course, there is all of the normal tourism of people visiting New York. And the biggest kicker of all, it is just so expensive to live in New York that renting out all or a portion of one’s apartment or home is often necessary for many people just to make ends meet. Rents are staggeringly high in New York, with the average 2-bedroom apartment going for $5,250/month! Why not rent out that second room?

But those very same rising rents were a catalyst for local officials in New York City (fueled by constituents) to take measures to make housing more affordable. And that is how the idea of restricting short-term rentals became en vogue with the belief that any time a rental unit is converted into a short-term rental, it is taking a place to live away from a long-term renter. As the supply of long-term units is constricted, rents go up, New York City officials and many others believe.

The notion of regulating short-term rentals in New York City is not a new one. Both New York State and New York City actually enacted restrictions prior to the January 2022 rules like in 2016 when New York State passed the New York State Multiple Dwelling Law, which laid out a whole series of provisions that were meant to rein in the short-term rental market. The problem was that there was mostly non-compliance from operators and non-enforcement by municipalities. As rents continued to rise, the urgency to take action only increased in the interluding period.

The Battle

San Francisco-based AirBNB, which is now a multinational corporation with a market cap of over $90 billion, has been at the forefront of fighting these regulations. If you want to read through an interesting run-down of the relationship between AirBNB and the City of New York, Skift.com has a good overview here that was actually compiled by an AI bot (!). But suffice it is to say, it has been a rocky road for AirBNB in New York, only the more so lately; just last month a judge threw out AirBNB’s most recent lawsuit against the City, calling the City’s efforts “entirely rational.”

The Kill Switch

The January 2022 restrictions on short-term rentals that started to be enforced this past week are, indeed, quite pointed. Not only must all short-term rental operators register with the City and pay a $145 fee, but the host must actually own the apartment as their primary residence and must be on site during the visitors’ stay. The maximum number of guests is two, and all areas of the interior of the apartment must be accessible without locks on the interior doors (in other words, guests are meant to have access to the full space). Approved short-term rental operators will have their names and unit addresses published on a publicly available searchable website. Penalties for non-compliance can include fines up to $5,000, and the companies themselves like AirBNB and VRBO will also incur fines and other penalties for making listings available on their sites from non-approved operators.

As noted above, AirBNB and others have launched a series of lawsuits against New York City, but with the latest dismissal, it seems that the battle is basically over barring some appeal to a higher court or a radical shift in policy at the municipal level of government in New York City, the latter which is especially unlikely.

What Comes Next

The courts have signaled that not only do they not find merit in AirBNB’s arguments that the restrictions are too severe and inhibit property owner’s rights to do what they choose with their property, they don’t even want to even entertain it anymore in a courtroom. The effect in New York City has been a sharp decline in AirBNB listings.

New York City did set up a mechanism for short-term rental operators to apply for a license in order to continue offering short-term stays, but as of August 28th, the City had only approved 257 permits out of 3,250 applications. According to one source, there were previously over 40,000 AirBNBs in New York City. The new regulations will wipe most of those away entirely. A quick look at the map of available AirBNBs in New York City over the upcoming Thanksgiving weekend, for example, shows pretty slim pickings, at least relative to what it would have been in previous times:

What is also a certainty is that hundreds of other cities and towns large and small around the country are watching what has happened in New York City. As I’ve written about before, many local officials have already started enacting restrictions against short-term rentals. This makes this asset class risky for investors as it is just impossible to predict what will happen on a town-by-town basis. Whether they operate in Newcastle, California or Newcastle, Maine, owners of existing short-term rental properties would be wise to start advocating to their local officials that they should at least be grandfathered in when the restrictions start to hit.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Weekly Round-Up

Here are a few things that caught my eye this week:

A Vermont man has to pay back $660,000 of fradulently obtained PPP loans and serve two years in prison for falsifying records and misusing these pandemic-relief funds. Read more via The Bangor Daily News.

Two weeks ago I wrote about how many homebuyers are simply giving up and commented that many younger homebuyers could be getting down payment contributions from older family members including parents. A reader followed up to send me this article by Athena Botros of Fortune showing that a whopping 40% of homebuyers under age 30 are getting financial support of this kind (sorry, the full article is behind a paywall…but you get the basic point).

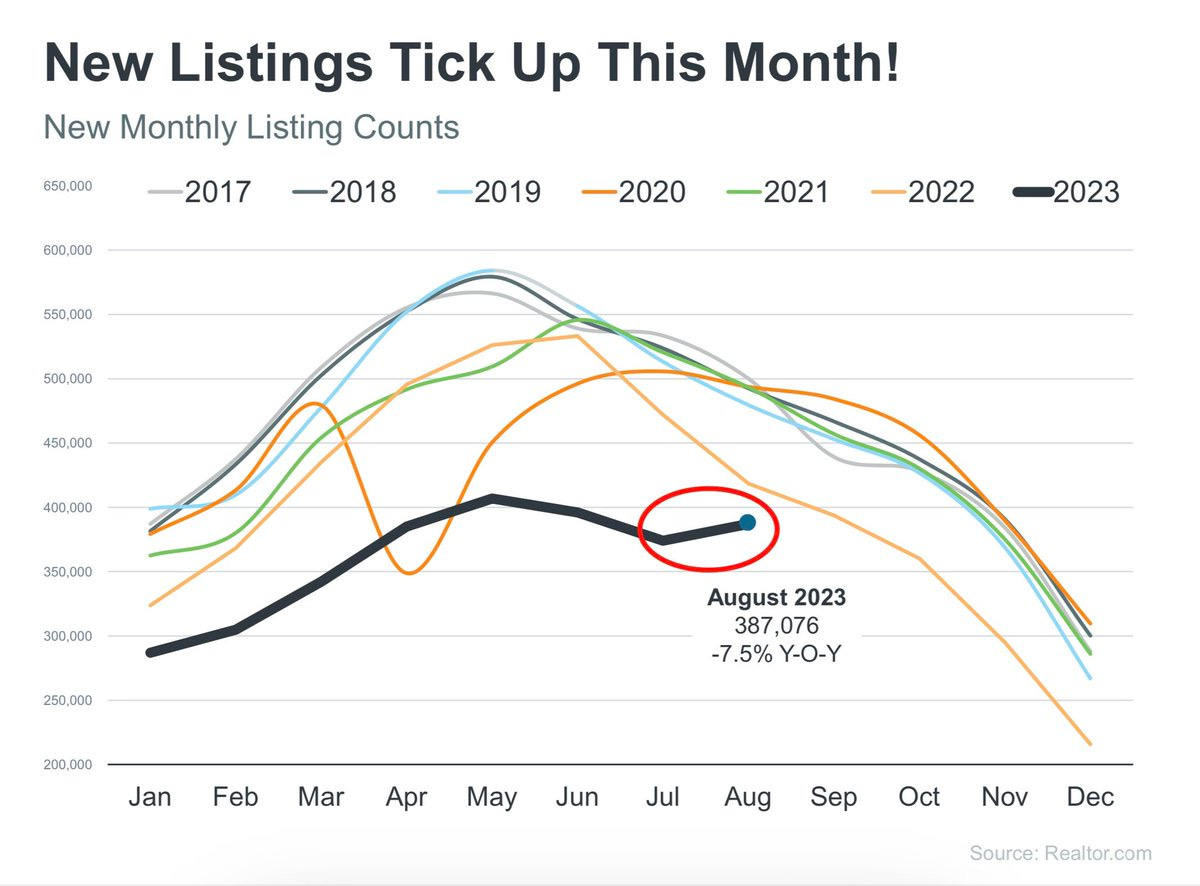

Via Ryan Lundquist on X (formerly Twitter) using data from Realtor.com, home listings were up in August, which is usually a month when listings are dropping as we head into the fall.

Have a great week, everybody!

Seems to me that the problem is with the assumption that if an apartment is not listed for short term rental that it will be listed for long term rental. That's a proposition that should be given a reality check. Elsewhere most of the opposition to AirBNB comes from other proprietors in the short-term accommodation market like motels and hotels. Protecting one seller from the competition offered by another seller limits consumer choice while enabling higher prices to be charged. Comes under the heading of a restraint on trade. Adam Smith observed that: 'People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.'

The fundamental problem relates to supply, that in turn relates to the difficulty attached to redeveloping an old city and the cost of travel, and amount of time lost in travel when a city gets too large. That results in price inflation. The remedy is to allow the building of an alternative settlement elsewhere. Good luck with that because those with a stake in the city will be against it and they will have the planning fraternity in their pocket.