Retail Market Shows Signs of Softening

What it means for the economy, inflation, and interest rates

The weeks between Thanksgiving and New Years may traditionally be thought of as the time of year that retailers make their money, but for many businesses especially in tourist-centric areas of the country like the one from where I write here in Maine, the make-or-break period is actually the 99 days from from Memorial Day to Labor Day. Sure, the shoulder seasons matter too, and some of the traditional seasonality in retail has been dampened by the shift of spending to the internet. But for many businesses and their owners who make a living selling things to consumers, summer is the time for that cash register to ring.

One thing I have been hearing from a lot of the business customers I work with so far this summer is that things are not especially strong or especially weak, but perhaps just a bit soft. No one is panicking and numbers are not deteriorating, but whether it is restaurants, retail, grocery stores, or other types of consumer sales, this season has just not felt super strong. I felt terrible for many of the businesses in Bar Harbor, Maine a week ago Saturday when my wife and I were spending the weekend there. We walked around town on what should have been one of the biggest nights of the year in town (the Saturday before the Fourth of July), and it was 58 degrees, raining, and regrettably rather quiet.

The fickleness of the weather aside, does this softness represent a material decline in the economy? Or is it just normalization after a particularly robust, inflation-and-stimulus fueled sugar high of the past few years? Let’s look at the data to dig in.

The Quantitative Side

We’ll talk about the vibes in a minute, but from a purely quantitative standpoint, consumer spending is softening. The latest Commerce Department report on personal consumption expenditures showed that spending in May was up 0.1% over the previous month, and up 2.6% on a year-over-year basis. That figure is less than that of overall inflation, and is also the slowest rate of personal consumption spending since March 2021. The following chart via CNBC shows the trend downward in spending over much of the past two years:

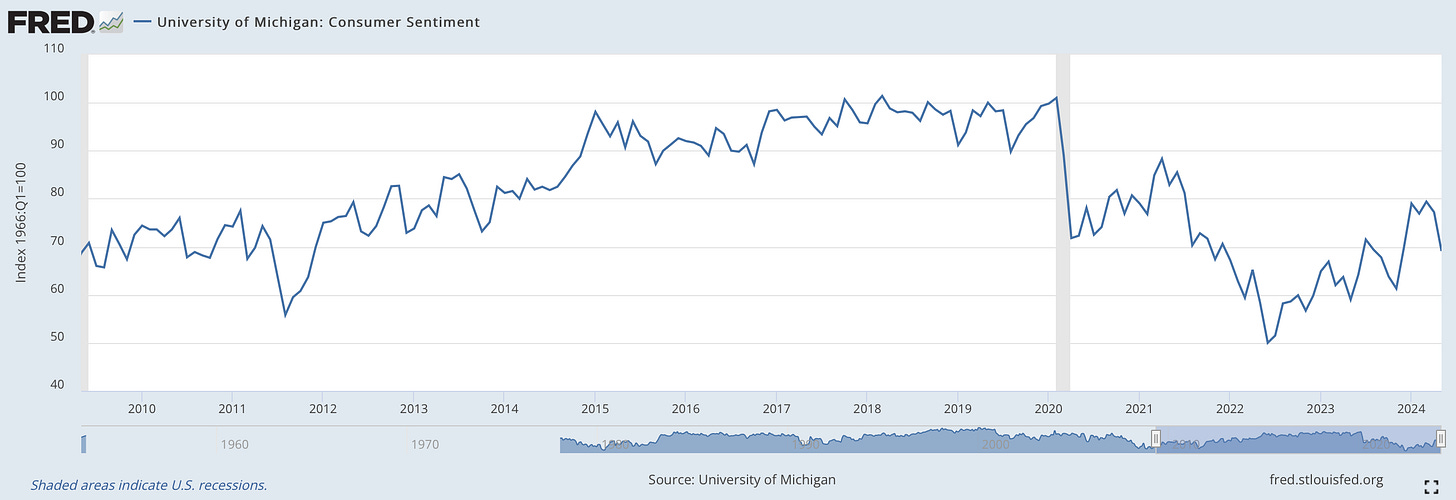

Consumer sentiment in May remained generally low. Although still up from its 2022 trough, the chart below of the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment survey over the last fifteen years shows that sentiment has generally been down since the outset of COVID-19 and has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels. We may actually be in a permanent era of poor consumer sentiment, which I attribute to the ubiquitousness of social media and its algorithms, toxic political tribalism, and a general feeling of exhaustion out there (more on that in a future article).

Consumer sentiment readings must be taken with a grain of salt, however. It would be intuitive to say that when people are not feeling positive about the economy, they are less likely to spend money. That has not played out for much of the past four years, however, as sentiment has been down but spending has been up, part of a weird juxtaposition of feelings vs. behavior.

I don’t necessarily have data to support this, but I fully suspect a large part of the bad vibes out there right now are specifically because of the particularly high prices at the grocery store. Although food inflation today is only running at a rate of 2.1% on a year-over-year basis, which is actually less than the rate of overall inflation, the rate of food inflation was 3.9% in 2020, 6.3% in 2021, and 10.4% in 2022. People are still really feeling that. People remember when their usual basket of goods at the grocery store was, say, $125/week, and now it’s $160/week and they are angry about it (and also cash-strapped).

Interestingly enough, a recent McKinsey study found a bit of a generational gap in feelings on the economy, but not necessarily the one you might expect. The authors report:

Younger consumers were more optimistic about the economy (optimism rates for Gen Z and millennials were 41 percent and 38 percent, respectively) than older consumers (optimism rates for Gen X and baby boomers were 29 percent each).

The report also found a high number of consumers buying less expensive versions of the same similar products, likely as a cost-saving mechanism:

Last quarter, most consumers continued to trade down—reducing the quantities they bought, searching for better prices, or delaying purchases—as they did for much of last year. This occurred across generations, although more Gen Zers and millennials reported trading down this quarter compared with last (to be sure, these consumers, particularly Gen Zers, also selectively splurged).

37% of consumers say they changed retailers for a lower price or discount, while 33% said they delayed a purchase because of price concerns; both statistics are up slightly from the same quarter of 2023. Despite the general pullback, there is also some splurging going on, however. Per the report, 39% of consumers report they are willing to selectively splurge on dining out or going to a bar, which was the most common splurge item/experience, with groceries, apparel, and travel also showing some “splurging strength.”

The authors of the McKinsey report conclude as follows:

The United States may be seeing evidence of consumers on the cusp of a shift as optimism about the economy declines, trade-down behavior continues, and consumers pull back their spending on nonessential goods.

National Bellwethers

The softer sales market is starting to show up in the earnings reports and shareholder calls of several bellwether American businesses. Consider the following:

First quarter sales at Target were down 3.7%. In-person sales were down 4.8%, but digital sales were up by 1.4%. Target CEO Brian Cornell said they are hearing the most complaints from their shoppers around pressures in groceries and household items.

Sales at Carmax were down 11.3% in the first quarter. The earnings report cast a dour note, saying, “We believe vehicle affordability challenges continued to impact our first quarter unit sales performance, as headwinds remained due to widespread inflationary pressures, higher interest rates, tightening lending standards and prolonged low consumer confidence.”

At Starbucks, North American sales were down by 3%, although this actually reflected a 7% decline in comparable sales that was partially offset by a 4% increase in prices. CEO Laxman Narasimhan called it “a highly challenging environment.” (Sidebar: for a great podcast episode about the founding of Starbucks and the early years of the company, check out this episode of Acquired or find it wherever you download your podcasts; it was a great listen).

The numbers and commentary from these CEOs (and numerous others) reflect a retail environment that is tough to navigate and contains some foundational softness. What does this mean for the U.S. economy going forward? Consumer spending is a huge portion of GDP. If spending drops (and it certainly seems at the moment like spending is moderating if not quite outright dropping yet), it will ripple through with a dampening effect on the overall economy. That is in many ways what the Federal Reserve actually wants to see in order to eventually bring down interest rates.

There is more weakening pressure on the economy right now than strengthening pressure, even if the economy overall does remain quite strong. Fore example, the most recent jobs report from this past week showed an increase of 206,000 jobs in June, but an unemployment rate that has ticked up from 3.8% in March to 3.9% in April to 4.0% in May to 4.1% in June. You can see where that is going: the unemployment rate will likely be in the 4.5%-5.0% range by the end of the year. That is still not a bad rate, per se, but it may be enough to trigger at least one quarter point interest rate cut by the Federal Reserve in the fall. The Fed continues to strive for that so-called soft landing where they can keep rates high enough to rein in inflation, but not so high that they lead to widespread job losses as a result of a major economic downturn.

Lastly, of note, in a year where the stock market has been generally strong, shares of some of the major retail giants have struggled. Nike is down 29%. LuluLemon is down 41%. Starbucks is down 18%. McDonalds is down 15%. Home Depot is down a more modest 3%, but still down in a year where the S&P 500 is up 17%. One notable retail outlier is Walmart, which has seen its shares actually rise by 32% since the start of the year. Another (and a special case, for sure), is Amazon, which closed the day on Friday at exactly $200/share, an all-time closing high. Amazon is up 33% for the year. Walmart has made great gains in its digital sales over the past few years, which is undoubtedly a major aspect of its growth. And Amazon is, well, Amazon. Other than for the most niche of products, retailers that are not leveraging up on digital are at risk of the world (i.e. the consumer) leaving them behind. Time will tell if the recent softening in the overall retail market is the beginning of a prolonged trend or just a blip on the radar.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Weekly Round-Up

Here are a few things that caught my eye this week:

A few weeks ago I wrote about the United States Supreme Court taking up the topic of whether cities and towns can prevent homeless people from camping in parks and other areas. The Court issued its ruling last week, saying that municipalities can, in fact, enact limitations on public camping even if there are no other places for the the homeless to go. The ruling is expected to have wide-ranging impacts and it thought to be the most significant Supreme Court case on homelessness, possibly ever. Nonetheless, there were both progressive and conservative advocates for Supreme Court action as there was a need to clarify what cities and towns can and cannot do.

Via Matthew Goldstein of The New York Times, some banks are quietly unloading loans secured by commercial real estate (office buildings, specifically) because of fears of future losses as the loans come due. Although the loans being sold right now only represent a “sliver” of the overall market, Goldstein says, “It’s an early but telling sign of the broader distress brewing in the commercial real estate market, which is hurting from the twin punches of high interest rates, which make it harder to refinance loans, and low occupancy rates for office buildings — an outcome of the pandemic.” Read more here.

On the topic of weakness in commercial real estate, San Francisco is the so-called epicenter of the collapse. But at least one person is buying: Ian Jacobs, a former Warren Buffett protege, who has pooled $75 million in funds from family members and others to scoop up San Francisco real estate he believes he is getting on the cheap. His plan is to wait until the technology sector leads to a resurgence in demand for San Francisco real estate. Read more via Fox Business.

Via Elizabeth Bernstein of The Wall Street Journal, people are scrolling through Zillow as a form of escapism/therapy. Sorry, the article is paywalled, but it is a pretty good read.

Have a great week, everybody!