The Complicated Question of Where Interest Rates Are Going

Plus: a look at Trump's pick to lead the Fed

The conventional wisdom out there is that interest rates are likely to come down in 2026, and that the downward momentum may continue right into 2027. This sentiment comes as welcome relief to beleaguered borrowers and would-be homebuyers who have been fed up with the higher interest rate environment over the past two years. But is it true? Are rates going to continue going down? Let’s take a look.

How Far We’ve Come

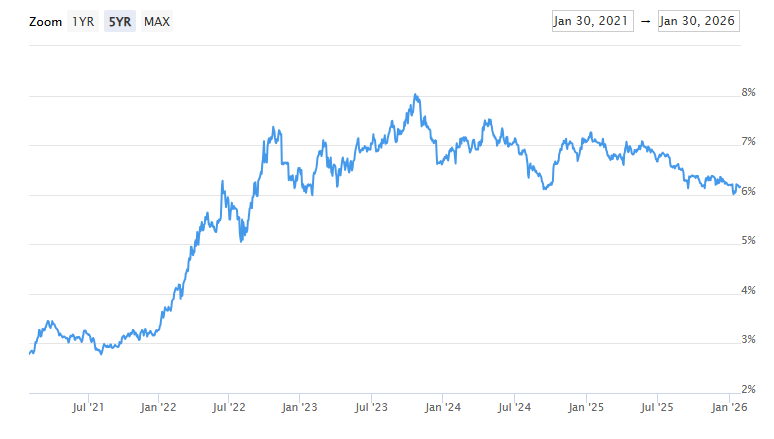

From a pure rate standpoint, the absolute “worst” time to lock in a home mortgage rate would have been October 2023. The average 30-year fixed rate nationwide peaked at exactly 8.00% that month. It has dropped fairly steadily ever since to just a tick over 6.00% today, as shown in the chart below:

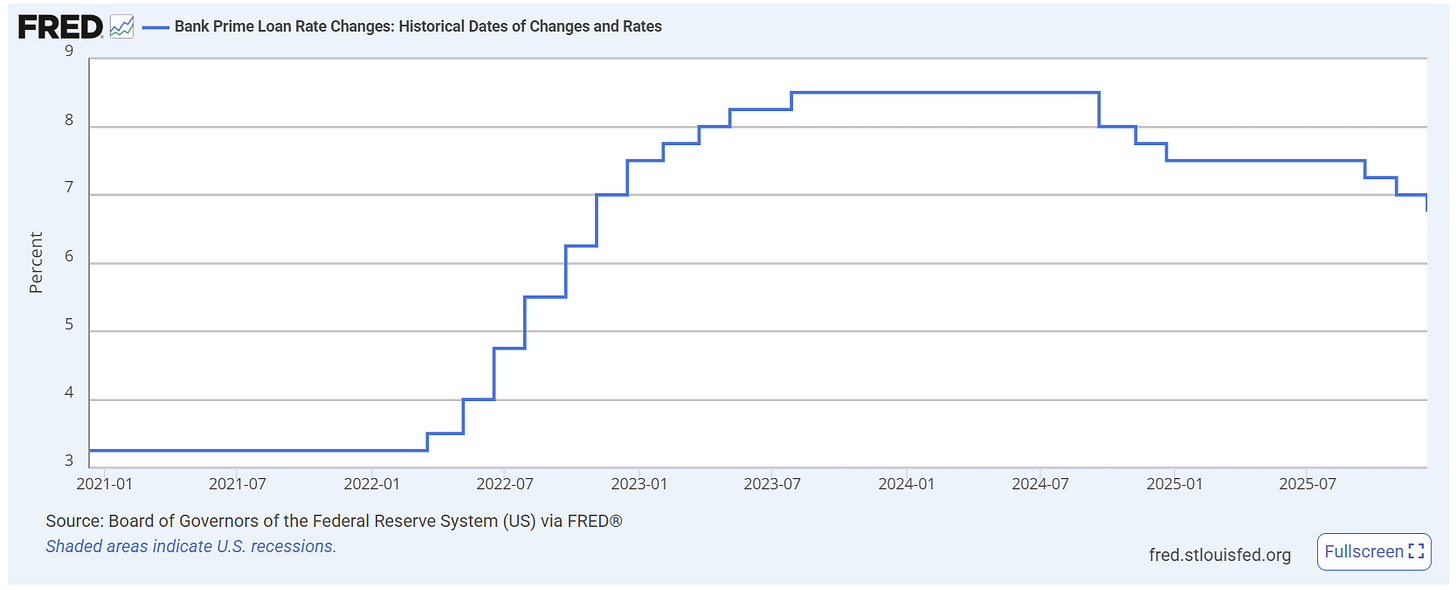

On the commercial side of the borrowing world, rates have also come down. Banks often peg their rates for business loans at a certain margin above a set index, such as the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) or the Fed’s Prime Rate. These rates are not subject to the same degree of fluctuations as home loan rates, but the peaks and trajectories have been generally the same as those on the residential side over the past two years. These indexes (and therefore the commercial loans that they are priced around) generally peaked in the summer and fall of 2023, and then stayed elevated for a full year until the fall of 2024, when rates started to gradually step downward. The chart below shows the Prime Rate, which peaked at 8.50% and has since dropped to 6.75%. This means, generally speaking, that it is cheaper to borrow for a business loan today than it was from the summer of 2023 through most 2025:

You can also see in the five-year chart above just how low Prime Rate was from 2020-2022 (the far-left side of the horizontal X-axis). Prime Rate bottomed out at 3.25% for several years during the pandemic before starting its climb, which made for some very cheap borrowing during that time period.

A brief word on savings rates before we look at the months to come: As a commercial lender myself with an eye on the real estate market, I tend to focus on interest rates on loans. But there is another side of the interest rate equation, and that is the interest rate yield for savers. The trajectory of savings rates generally matches the charts above for borrower rates, in that for most of the 2010s and early 2020s, interest rates on savings accounts were very low. Rates rose from 2022-2024, but have been easing back down over the past 6-12 months. The national average money market rate peaked in May 2024, and has been steadily declining since, per data from the Fed. While borrowers may be pleased with falling rates, savers undoubtedly are not, especially with sticky inflation eating into much of that savings yield.

The Year Ahead

To pull a joke from an Econ 101 textbook, what is the answer to any economics question? “It depends.” The trajectory of interest rates for the rest of 2026 certainly does depend on a few key factors, some of them economic and some political.

First, on the question of economics, it is worth a quick review of what the Federal Reserve is charged with doing. The Fed has a dual mandate: to promote a labor market with maximum employment (i.e. anyone who wants a job can reasonably find one), and to keep inflation low and stable so that money holds its value. On the latter question, the Fed’s general goal is an annual inflation rate of 2.0%.

These two mandates sometimes run in conflict with one another, especially once politics gets layered on top of things. You could have a poor labor market where unemployment is rising, economic growth is tepid, and inflation is high, a condition known as stagflation and something the U.S. suffered through in the 1970s and early 1980s.

What is the Fed to do in such a scenario? Bring rates down to boost the economy, which raises the risk of further inflation? Or clamp down on inflation by hiking interest rates, which risks tightening the overall economy and making the labor market even worse. In the 1970s and 80s stagflation era, the route the Fed took was to raise rates dramatically while simultaneously limiting the money supply, which eventually crushed inflation in the process. The cost was two painful economic recessions in the early 1980s and an interest rate environment in which people were borrowing for houses at rates of nearly 20%, but the economy did eventually get back on track and the Fed gained credibility after the painful, but ultimately successful, process of taming inflation.

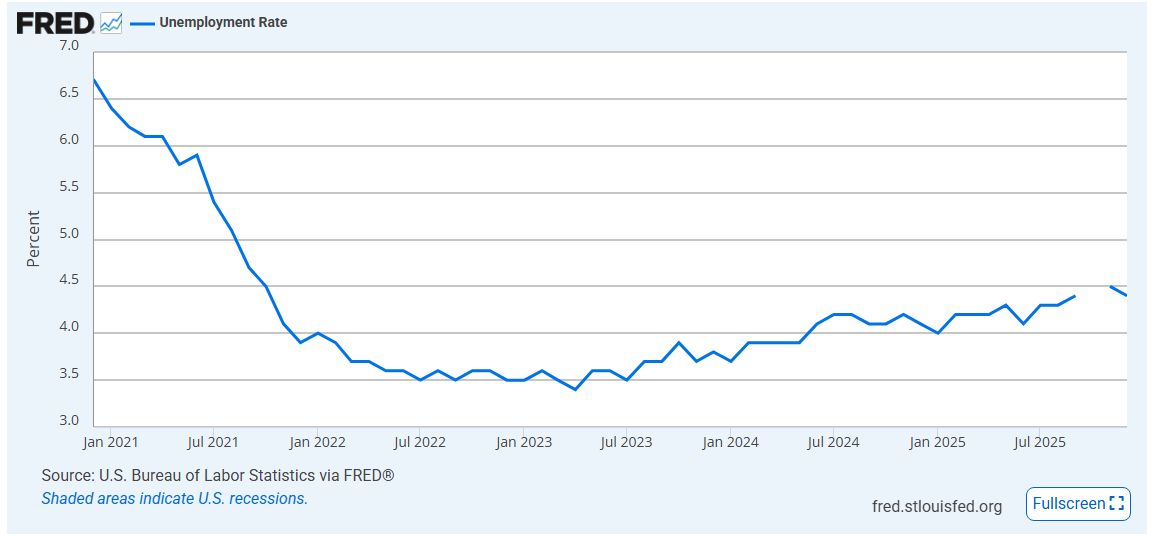

So where does the Fed find itself today? On one side of its mandate, the labor market (at least on paper) is moderately strong by historical standards. The December 2025 unemployment rate of 4.4% is not bad, although it has been ticking up for the past two years, slowly but steadily, as shown in the chart below:

As a quick aside, it is always going to bug me that there will be gaps in these graphs due to the government shutdown this past fall, in which data collection and analysis ceased for several weeks. I don’t think I’m an OCD-personality type completely, but that gap in the line on the far-right side of the graph is really driving me nuts.

But back to the lecture at hand: Ask anyone you know out there who is looking for a job or feeling job-insecure, and they will probably tell you that labor market is not strong. For starters, some of the pandemic-era over-hiring that happened is normalizing through attrition and layoffs, which has some people feeling pressure. And second, and quite notably, there is tremendous awareness out there all of a sudden of the massive threats that AI has to the traditional workforce. We are starting to see layoffs all over the place, particularly in the tech field, as tasks and responsibilities are increasingly moved to AI bots and algorithms. That is understandably making people nervous (and it should).

But I would submit that the other reason the job market feels so weak to people actually has more to do with inflation than jobs. People are feeling unstable at their jobs because the purchasing power of their dollars they are working so hard to earn has declined by so much over the past few years. You might be working (and most Americans of working age are), but it might not feel stable when your dollar just doesn’t go as far as it used to. And that’s a problem for the Fed’s other side of its dual mandate, because inflation has just not gone away.

Remember above when I mentioned the Fed’s goal is an annual inflation rate of 2.0%? We have not actually seen a single month where the year-over-year inflation rate was 2.0% or less since nearly five years ago in March 2021, when the inflation rate was 1.7%. In the 57 months since, inflation has been over 2.0% every single month. Sure, it is down significantly from the 2022-2023 peaks, and inflation has been running at a comparatively cooler rate of 2.5-3.0% for much of the past year, but it just hasn’t quite been stamped out. People are feeling it.

What Will the Fed Do?

So, faced with an employment market that, again, on paper at least, looks okay, but an inflationary environment that is still a bit too hot, what will the Fed do? Those who closely watch the Fed are divided on this question:

JP Morgan recently forecasted no rate cuts at all in 2026, unless inflation eases more than expected.

Analysts in a Bankrate survey project two rate cuts this year.

Independent forecaster Mark Zandi has predicted three cuts this year, likely of 0.25% each.

One tool I watch closely myself (the CME Group FedWatch tool) has a 7% chance that the Fed will keep rates the same this year, a 24% chance rates will drop by a quarter point, a 33% chance rate will drop by a half point, and a 23% chance rate will drop by even more than that. In other words, it’s kind of a muddled picture. Of note, however, while I have heard a lot of people speculating that the Fed would hold rates even in their January meeting (which they did), there has been a belief that they would drop rates again in their next meeting in March. The CME FedWatch tool has only a 13.4% chance that rates will drop in March, and an 86.6% chance rates will be held the same.

The Federal Open Market Committee, which is the body that makes decisions on rates, has twelve voting members, with four members rotating on and off annually. The Fed Chair always gets a vote. According to an analysis by Wells Fargo, the current group of twelve includes four voters who are relatively neutral, six who are likely to be more inclined to rate cuts, and two who are more inclined to hold the line (or even raise rates). That combination suggests, on net, a gradual easing of rates throughout 2026.

But there are a lot of politics involved here, for sure. For starters, Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s term ends in May. President Trump, who gets to appoint his successor, has clearly indicated regularly and aggressively that he wants to see rates come down. Just this past Friday, he announced his pick of Kevin Warsh to lead the Fed. Warsh was a previous Fed Governor so he has plenty of experience in this area and, in fact, has been seen by some as relatively hawkish on rates, suggesting maybe he won’t be as aggressive in bringing them down as people might think. Nonetheless, it’s hard to imagine Trump appointing him if he were not going to be inclined to do so. All that being said, the Fed Chair alone does not get to decide rates, and he would need support from other Fed policymakers in order to be able to do so.

We do have some data and comments from others on the Fed’s Open Market Committee that provide some insights into their thinking. For starters, when the Fed met this week, they voted 10-2 to keep rates the same. The two dissenting votes were both in favor of lowering rates now and not later in the spring, so there is already a toehold of interest in bringing rates down.

But there is a clear mix of opinion. On Friday, for example, St. Louis Federal Reserve President Alberto Musalem noted he does not see a need for immediate further reductions in rates, saying, “With inflation above target and the risks to the outlook evenly balanced, I believe it would be unadvisable to lower the rate into accommodative territory at this time.”

On the other hand, U.S. Federal Reserve Vice Chair Michelle Bowman said on Friday that she sees a possible need for three rate cuts this year of 25 basis points, saying, “The labor market is fragile…we should not imply that we expect to maintain the current stance of policy [i.e. keeping rates where they are] for an extended period of time.” Bowman did vote this week to keep rates the same, so she was not one of the two votes against the current stance, but it is clear she is open to cutting rates as soon as the Fed’s next meeting on the topic, which will be in March, or soon after that.

What Comes Next

The question of what the Fed will do ultimately comes down to economic conditions (i.e. employment and inflation) with this layer of politics over it. It is, of course, highly plausible that economic conditions do call for rate cuts and that being what the president himself wants does not preclude the Fed from making that decision. It is regrettable that in some circles, no matter what the Fed does, it will be seen as political. If the Fed holds back from cuts, it will be interpreted by some as a rebuff of Trump. If the Fed cuts, it will be seen by others as giving in to Trump. Hopefully whatever happens, the Fed can articulate through its statements, tone, and general temperature that it is striving to guard its independence.

If I had to call it, I would say the Fed will cut rates by a quarter point 2-3 times this year. That is just based on my general feel of how the labor market, inflation, and politics of it all will blend together. But, of course, it depends. There is a lot going on in the world, lots of it bad.

There are major tail-end risks here, too, that savvy observers and investors should be mindful of. One of these risks is that rates do come down significantly, which would give a boost to the economy (exactly what President Trump wants leading into the mid-term elections). But the risk is that this boost is a sugar high, and not real systemic economic improvement. The possible outcome of just such a sugar high is a relapse of that very same inflation that we have been fighting our way through for the past several years.

The other tail-end risk is that it is just impossible to know what the labor market is going to look like one year from now, three years from now, five years from now, etc. I wrote several times about AI last year and the impact on the ways we think and do business, and I have some real worries. If we get a workforce wipeout along the lines of what some have suggested is possible (e.g. the CEO of Anthropic has said the unemployment rate could reach 20% due to traditional workplace jobs being done by AI), that will result in an economic landscape well-beyond the tools of the Fed to react to. It may require legislative and executive action for our country (and, indeed, the world) to successfully navigate.

Home Loan Rates

Lastly, I regret to inform you, especially if you or someone you love is trying to buy a home, that even if the Fed does bring rates down in a notable way in 2026, it does not necessarily mean that home loan rates will continue to drop. Quite positively for the market, home loan rates have come down pretty notably in the past two years, as shown in one of the charts above (i.e. from about 8.00% to about 6.00% on the average 30-year fixed mortgage). But home loan rates are not based entirely on what the Fed is doing, but rather on how banks themselves price their loans, which is based on supply and demand, competitive pressures, and the bank’s outlook on future rates and inflation.

Home loans are generally sold and repackaged on the open market as investments. If the investment market believes inflation will be higher in the future than it is today, it will demand higher rates on these home loans now as investments. We don’t like to think of home loans as being investable assets and, believe me, I get that, but that is how the bank home lending market generally works. If an investor can get, say, 5% on a U.S. Treasury Bill, which is virtually risk-free, they will demand a higher yield on a pool of mortgage loans, which are not risk-free. That is why if inflation persists and even starts to rise again, home loan rates aren’t likely to come down much farther than where they are now. The best thing to get home loan rates to fall is a continued cooling off of inflation, and a more stable economic environment in general. The Fed has a role to play in that, but so too does the President and Congress.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com. Thoughts and opinions here do not represent First National Bank.

Thank you, Ben! I remember purchasing my first home in 1975 for $25,000 at a rate of 17% interest. ( It won’t surprise you to know that it was a rundown 1825 home in need of restoration.). If you have need for writing suggestions, I would love to read your thoughts on the price of homes then and now, adjusted for inflation and the income of wage earners. It seems that two-wages were needed by 1975 for middle income first time buyers and as you wrote, the economy was unstable. (Another subject would be about what seems to be nearly predictable cyclical good and bad times ) Nancy

Excellent piece; a comprehensive and insightful look at economic mechanics that far too few are looking at or properly understand. I agree with your rate cut prediction generally as well.