The Looming Critical Thinking Crisis

And what will matter in the classrooms and workplaces of the future

In tiny towns, big cities, and communities of all flavors from Maine to California, kids are headed back to school. Yes, technically even here in the cool, crisp Northeast, we should still have a good month of warm weather left, but once it starts to get dark at 7:15 pm and the Friday night lights at the local field come on for high school games, it might as well be fall. Labor Day Weekend is here, and with it, summer is over.

This Back-to-School season brings a host of pressing questions for students, parents, and the field of education in general. Public school enrollment is declining, absenteeism is rising, and retaining good teachers is becoming harder. Communities are strapped for resources. Many teachers feel drained by escalating student (and even parental) behavior issues, the constant fight against screen distraction in the classroom, and a broader malaise hanging over the profession if not outright antagonism in certain quarters.

Any one of these topics would be worth delving into deeper. But beyond the frustrations encapsulated in the above issues, there is a bigger change at play in the field of education and, truly, in how we all think, and that is how AI is changing the ways we seek, analyze, and synthesize information.

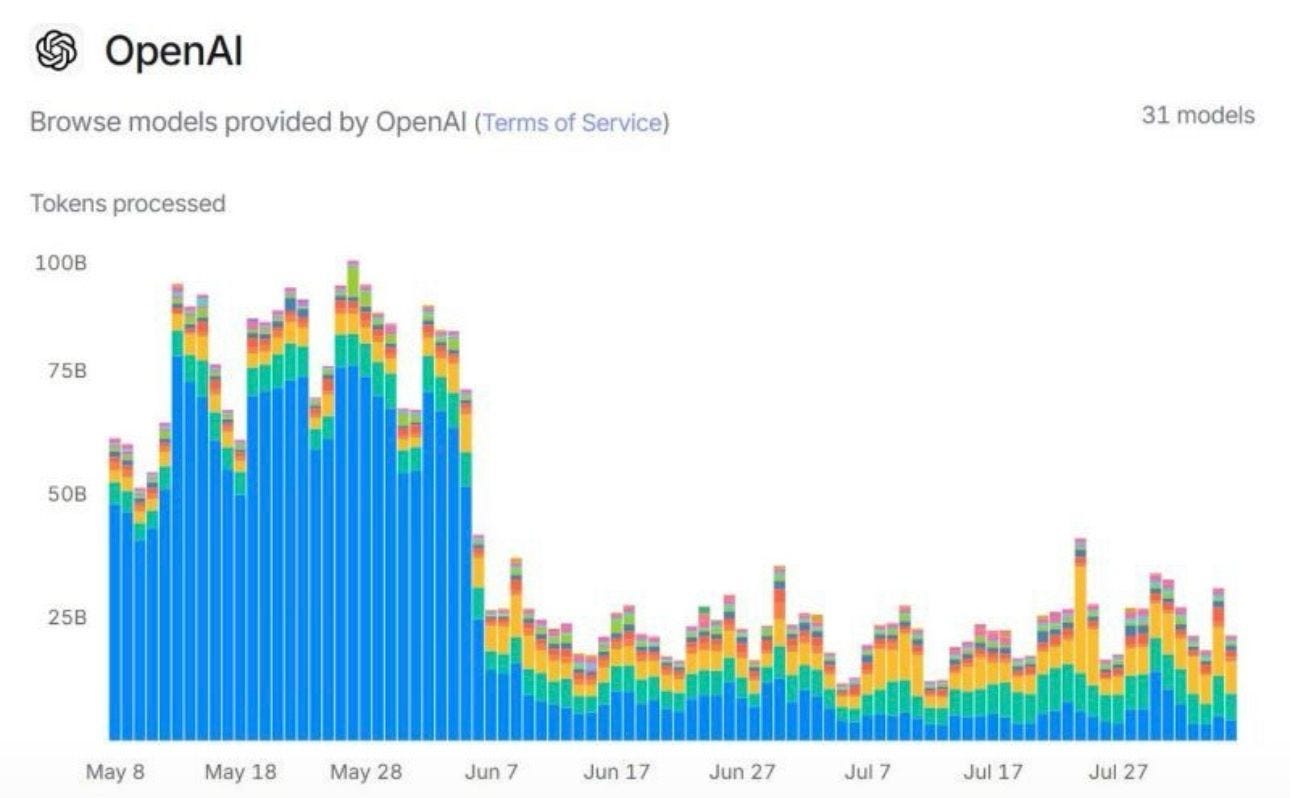

While scrolling the web this week, I was struck by a chart showing the cliff of AI usage in the early days of June (it also shows drop a bit on weekend days earlier in the spring). See below:

The most likely reason for the drop-off is the end of the school year — there is no homework in the summer, no tests to prepare for, and no papers to write (unless you’re a Substack writer with a weekly column). I expect that a chart showing the subsequent months of AI usage will show a spike at the end of August and beginning of September as students get back into it.

I have seen some discussion threads about the use of AI pondering whether ChatGPT and the like are just fads or whether they will stick. After all, doesn’t the chart above sort of show how people are using AI for certain things (in this case, schoolwork), but that as soon as that thing is no longer in play, AI is not necessarily a part of everyday life.

What I am seeing among not just young people (although, yes, students in particular), but people of all ages, however, is not just adoption of AI for various tasks, but the beginnings of AI dependency and, with it, the potential evaporation of critical thinking abilities.

I wrote earlier in the summer about how tools like ChatGPT have become the fastest adopted technology in history. Just to give two data points: a 2023 survey found that 30% of college students used ChatGPT to help with schoolwork in the 2022-2023 academic year. More recent data, however, shows 64% of students are using ChatGPT, with an even more astounding 86% of students using AI tools in general including Grammarly, Kortext (a note taking app), DALL-E (image generation). In other words, nearly all students are now using AI for help and support in their schoolwork, if not for outright delegation of that work.

Not that this is necessarily all bad. AI is a tool, and much like other tools such as calculators, computers, and the internet, technological advancements, of course, make various aspects of modern life easier and more convenient. I wrote recently about how I use ChatGPT in helping to support this Substack series. I don’t ever see not using it as a research assistant and proofreader as I write.

I am old enough to remember going to the Bangor Public Library on a Saturday afternoon to do research for school projects. You had to look up your topic in the card catalogue, write down the number of the book you wanted about gorillas or ancient Egypt or whatever, go find it in the stacks, and then actually turn through the pages to find the information you needed. My family had (and still has) an actual set of encyclopedias on the bookshelf in the living room of the house where I grew up. Once a functional, useful, and commonly used set of books, they are now mostly there for decoration and perhaps also nostalgia. I have to think the rise of Google and Wikipedia put huge dents in the encyclopedia business (note: in further research while writing this article, I discovered Encyclopedia Britannica stopped printing in 2010).

But here is the problem with AI tools that help to gather, analyze, write, and answer questions: it’s so good at it. And yes, that is a problem, because it takes the requirement of deep thought away from its users. Learning about a topic, developing thoughts and conclusions, and organizing those thoughts into a paper (or, if the field is math, into a theorem or a dataset) is like putting a puzzle together. There is the payoff at the end of the finished product, which is rewarding and fulfilling in its own way, but the process itself exercises the mind in important ways that help to develop synapses and pathways. Deep thinking (the human kind) is an important aspect of personal growth. In fact, I would argue the ability to critically think is part of what makes us distinctly human. So what happens when the need to critically think is no longer there?

In the short term, we’ll probably see more polished essays, cleaner code, and sharper presentations from students than ever before. But we risk mistaking output for understanding. If a student never struggles with how to frame an argument, or never wrestles with how to solve a tricky math problem, they may miss the deeper learning that comes from effort, from trial and error, and from failure. Struggle is frustrating, yes, but it is also formative. It’s the quiet cave where resilience and genuine comprehension are built, not to mention the satisfaction and joy that come from achieving something that you had to figure out yourself.

What Will Matter

If the ability to generate work and develop conclusions becomes commoditized through AI, then what separates one student — or future employee — from another? Or a related question, what should students be learning in schools when the need for analyzing information is evolving as much as it is right now. And not just with AI, by the way, but with devices like Alexa and the like. If my kids don’t know the answer to 6 times 6, there is a device on the kitchen counter that can tell them the answer, instantaneously, on command. Information recall has always been a tenant of American public education - multiplication tables, yes, but also state capitals, the order of presidents, element abbreviations, and a thousand other factoids — what should teachers be teaching when information recall is so easy through the devices on the table, on our wrist, or sitting in our pockets?

To find a positive here, increasingly, it will be the human skills that matter most. The so-called “soft skills” that don’t really feel soft at all when you’re in the workplace: showing up reliably, contributing positively to a team, listening carefully, reading the room, and bringing humility, kindness, and leadership to the table. Being the person others want to collaborate with may end up carrying more weight than being the person who can produce the slickest presentation, especially when everyone has access to the same AI-powered tools. Being a kind and thoughtful person who shows up and gets along well with others is, of course, a good thing to be anyway, but in the workplaces of the future, these traits will be even more of the comparative advantages than they already are now.

Should schools teach more of these soft skills? I would argue the best schools with the most thoughtful teachers are doing it already. It is done in the thousands of interactions over the course of the school year between teachers and students, administrators and others. But it will be absolutely crucial going forward.

Workplaces, bosses, and managers need to understand the shift that is coming, too. An entire generation is coming of age addicted to the internet, and now, increasingly, dependent on it for developing thoughts, ideas, and conclusions. Many of the members of that generation are still in college or high school or even younger, but they will be the future worker base in just a few short years.

AI may well free us from drudgery, but the challenge will be making sure it doesn’t also free us from thought itself. As with past technological shifts, the real test will not be in how the machines perform, but in how we adapt around them. Tectonic shifts are happening as we speak, however, and the classrooms and workplaces of the future will need to shift, too.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Another well written piece on a serious issue. "But we are mistaking output for understanding." Striking. And then there's episode 3 of the current season of South Park...

Important topic - thanks for diving into it. Shame that i've already lost those critical thinking skills!