The Perils and Promise of Prediction Markets

One of my favorite movies is the 1994 cult classic comedy Dumb and Dumber, and one of my favorite jokes in that movie is when Harry tells Lloyd he doesn’t gamble, and Lloyd tells him, “Twenty bucks says I can get you betting by the end of the day…I’ll give you 3-to-1 odds.” After some back-and-forth, they shake on the deal, and Lloyd immediately starts scheming in his head about how he is going to get Harry to bet with him. “I’m going to get you. I don’t know how, but I’m going to get you!”

Gambling in America has a long and sordid history. From riverboat card games and backroom bookies to Las Vegas ballrooms and neon glows to state-run lotteries and horse tracks, betting has always existed in a strange moral gray zone. Gambling is simultaneously condemned, tolerated, regulated, quietly encouraged, and much beloved by many.

For most of the 20th century, gambling was officially frowned upon, driven underground by law but sustained by demand. Even when states began legalizing certain forms of gambling, the public posture remained cautious, as though gambling was a vice best kept to the edge of town and out of public view (and sometimes literally underground).

Now, in many states, you can gamble on virtually any professional or college sporting event around the world at any given moment from your living room, bedroom, or breakfast table. Gambling provides entertainment to millions of Americans, but also destroys lives in the same ways it always has.

Legal sports betting has become the vice of choice for millions of Americans, particularly young men. This a country that loves to bet, and has spent decades becoming more comfortable with which bets are acceptable and how those bets can and should (or should not) be regulated. The impact of sports betting on how Americans consume sports is worth its own article at some point.

That said, as we approach the pinnacle event of the American sports world, the Super Bowl, betting on sports has reached an all-time apex. With sports gambling now legal in 39 states plus Washington D.C., nearly $2 billion will be bet (legally) on the Big Game. Millions of Americans will be watching the Super Bowl not just to see who wins the game (or what the best commercials are), but whether Sam Darnold will throw an interception, whether Rhamondre Stevenson will run for more than 61 yards, or whether the game will end with an odd or even number of points. There are over 2,000 different unique things you can bet on in this one game, including countless live bets within the game that evolve and adjust based on how the game itself is unfolding.

Even as the bets roll in in record numbers, however, the sports betting market is facing some unexpected pressures. “Gambling” in the United States, and, as we will see, the term “gambling” is evolving, is entering a new phase with the sudden rise of prediction markets.

The “Bet On Anything” Era

First, a primer: what are prediction markets?

At their core, prediction markets allow participants to buy and sell contracts tied to the outcome of future events. A contract generally pays out $1 if an event occurs and $0 if it does not. If that contract is trading at 63 cents, the market is effectively saying there is a 63% chance the event will happen. If you bet and win, each “contract” you have purchased for 63 cents is worth $1 at the end, a profit of 37 cents per contract. Alternatively, if your pick loses, your 63 cent bet on each contract becomes $0 (i.e. worthless). Prices move as new information enters the system, and the collective judgment of thousands of participants, each with money at stake, produces a real-time probability forecast. For the Super Bowl, for example, you can buy contracts on the Seattle Seahawks to win for 69 cents, and you can buy the New England Patriots for 33 cents. This reflects the fact that the Patriots are underdogs, and you can buy them to win for less than you can buy the Seahawks.

The concept of prediction markets has existed in academic and experimental forms for decades, often quietly outperforming polls and expert forecasts. What is new is their migration into the mainstream, fueled by better technology, regulatory openings, and a public newly comfortable with wagering on events and circumstances far beyond the playing field. People want to bet, and they don’t just want to bet on sports.

You can now bet (or “purchase contracts,” to use the technical/regulatory term) on who will be the Democratic and Republican nominees for president in 2028. You can bet on a range of prices of where the S&P 500 will close the year. You can even bet on things like whether the Supreme Leader of Iran will be out by certain dates (contracts are trading at 9 cents that he will be out by March 1st, 20 cents he will be out by April 1st, and 38 cents that he will be out by September 1st). You can bet on which movie will win Best Picture as the Oscars later this month, and even who will attend the Oscars (Taylor Swift is currently an available bet at 22 cents, reflecting the market’s likelihood that she will not be in attendance; if she were expected to attend, her price would be something like, say, 80 cents). You can bet on what words and phrases the announcers will say on-air during the Super Bowl, or what Donald Trump will say in his next interview on Fox News.

The most prominent regulated prediction market in the United States today is Kalshi, founded in 2018. Kalshi is notable because it operates as a federally regulated exchange, overseen by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). Instead of positioning itself as a gambling platform, Kalshi frames its contracts as event-based derivatives. This jargony regulatory status gives Kalshi a legitimacy that few others can claim, even as it continues to test the boundaries of what counts as a “financial” event. Kalshi CEO Tarek Mansour has said, “The long-term vision is to financialize everything and create a tradable asset out of any difference in opinion.”

Then there is Polymarket, launched in 2020, which has exploded in popularity despite being technically unavailable to U.S. users. Polymarket operates offshore and uses cryptocurrency-based settlement, allowing users to wager on everything from geopolitical outcomes to cultural events. It is fast, liquid, and remarkably comprehensive, but it exists largely outside the American regulatory framework, and has drawn scrutiny from U.S. authorities. Odds are high that Polymarket will be fully available in the United States eventually, however. The NHL, MLS, and UFC have all done promotions with Polymarket, and live Polymarket odds were recently included on-screen at the Golden Globes on a trial basis. Again, this is a country that likes to bet, and you can bet on the fact that you’ll be hearing a lot more about Polymarket and Kalshi in the months and years ahead.

This is where the definitional debate begins to matter. Are these platforms gambling? Or are they tools for aggregating dispersed knowledge about the future (i.e. information markets)? The answer depends less on economics than on law and culture. Sports betting is regulated by gaming commissions. Prediction markets, when allowed at all, fall under financial regulators. The same act (i.e. risking money on an uncertain outcome) becomes something entirely different depending on the label attached to it.

And that distinction is becoming harder to maintain. As prediction markets expand beyond interest rates and elections into increasingly granular questions about the world, they begin to look less like niche forecasting tools and more like a new kind of betting ecosystem, one where you can wager not just on who wins the Super Bowl, but on how the future itself will unfold.

Of note, by the way, Kalshi, in my opinion, clearly provides a technical workaround for people who want to wager on sports but where sports betting is not legal. Sports betting is legal in 39 states, but, surprisingly, in my opinion, is not allowed in California and Texas (and nine other states), where voters and policymakers have rejected previous attempts to allow sports betting. But you can use Kalshi in Texas and California alike, and plenty of people in those states will certainly be betting on the Super Bowl through prediction markets. It’s quite a wide-open loophole, at this moment in time.

I think of my own state of Maine, where sports betting has been long debated and where there have been lengthy deliberations in the Maine Legislature and, more generally, in the court of public opinion. Sports betting is legal here, but is limited to only certain platforms like DraftKings and Caesars. But then, all of a sudden, Kalshi comes in, and anyone can “bet” there with very little regulatory oversight. It sort of makes you wonder. The burden of proof was so high for DraftKings to get into the market, for example, and then a prediction market like Kalshi comes in almost seemingly overnight with very little oversight or resistance.

The Promise

Despite the fuzzy legal framework and eyebrow-raising ethics of wagering money on world events (like the downfall of a world leader), proponents of prediction markets would tell you these “markets” actually play an important role. We live in an age where individual expertise is not valued as much and often not trusted or even respected. Newspapers have been doing away with editorial and opinion pages, with the belief that readers do not care as much anymore what subject-matter experts or social commentators have to say on important matters. There is also just a belief that these so-called experts are not often right, or that they are so biased towards one political view (and often getting paid to have that point of view) that it is impossible to trust what they are saying. Prediction markets, on the other hand, broaden the expertise and democratize the predictions.

How have prediction markets done? In the days leading up to the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election, for example, most media pundits and political observers pegged the Donald Trump-Kamala Harris race as essentially a 50-50 toss-up. Prediction markets starting tipping towards Trump in the last few days, however, providing a signal that there were some out there watching and analyzing the data in a way that the mainstream media and so-called experts may have missed or couldn’t see showing Trump with traction leading up to Election Day.

Politics and the presidential election aside, however, the real value in prediction markets is that they aggregate wisdom and insight from a broad pool of observers, or market participants. Decades of evidence to previous non-corporate prediction markets (which were largely in the academic fields) suggest they often outperform polls, expert panels, and forecasts made in isolation. That makes them useful not just for sports or elections, but for economics, public policy, science, and business planning. At their best, prediction markets reward being right rather than being loud, partisan, or persuasive. They don’t eliminate uncertainty, but they quantify it, and in a world drowning in overconfident (and often bombastic) takes, that alone is a public good, many would say.

The Perils

The rise of prediction markets does raise some important questions and concerns. First and foremost is that many people will certainly lose a lot of money betting on these platforms. According to one analysis of Polymarket users, 70% of users generally lose money, and the vast majority of gains go to a very small sliver of the market; 0.4% of users take home 70% of the profits. This is, in many ways, not too dissimilar from other betting platforms like DraftKings.

There is also just the concern, as alluded to above, that it feels uncomfortable to see people betting on world events that impact hundreds of millions or even billions of people, often detrimentally so. Prediction markets have offered “bets” around questions of whether certain areas of the world would experience famines or flooding, for example. It feels morally or ethnically suspect to bet on such a thing.

Proponents would flip these questions on their heads, however, and say that actually a broad market of localized, specialized expertise on environmental questions is quite valuable in that it can help policymakers and businesses plan and react to such crises. There are anecdotes of people in California looking to prediction markets to get an understanding of when wildfires would be fully contained as a way to know how much danger their neighborhoods were in. Prediction markets were seen (by some) as more accurate in these complex, high-pressure situations than talking head expertise on TV or in the government.

Ultimately, the Venn Diagram of prediction market supporters overlaps quite heavily with those with a libertarian sense of allowing people to do what they want, bet what they want, and experience the consequences of those bets as they unfold. In fact, the rise of prediction markets has largely been fueled by technologically savvy, libertarian leaning users who don’t have a problem putting their digitized and data-centric points of view up against the world. Many of these people just don’t care about the ethnical perils or pitfalls of betting on world events, for better or worse, or they can justify it by pointing out the actual value in such markets, as noted above.

The Insider Problem

There is one other reality of betting on these platforms that is not yet resolved, and may not ever be, and that is the problem of insider betting. Consider the following: in early January, a Polymarket bettor with a username of “Burdensome-Mix” suddenly bet over $30,000 that the president of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, would be removed from office before the end of January. That outcome came to pass when U.S. forces mounted a surprise operation and captured Maduro.

When the bet resolved, the trader walked away with a windfall of more than $400,000, roughly a twelve-fold return on their stake. One of the interesting things was how sudden and unexpected the Maduro bets were, and that they came from an unknown newly created account. That setup has led legal and financial experts, as well as lawmakers in Washington D.C., to speculate that the bettor may have had access to non-public or classified information about the planned operation. Such access, if true, would resemble insider trading (i.e. exploiting confidential knowledge for financial gain) albeit in a prediction market that operates with far lighter regulation than traditional stock or futures exchanges.

The event has ignited debate over how prediction markets should be regulated, with some lawmakers pushing proposals to bar government employees and officials from placing such bets when they have access to sensitive information. Critics argue that platforms like Polymarket lack the guardrails that exist in regulated financial markets, making them ripe for abuse if insiders take advantage of privileged intelligence.

The Maduro bets also raise the clear and simple concern of whether people with privileged, sensitive information about military operations are using that information to make a profit and, with it, risk revealing government secrets through their betting patterns.

For the integrity of the platforms, the insider risk is relevant to many other types of bets, too. You can bet on what Bad Bunny’s opening song will be during the Super Bowl halftime show. There are probably several hundred people who actually know what it will be; they have to plan these shows out, after all. And all of those hundreds of people have family and friends who might try to get inside information from them, any one of whom could then bet on these platforms. But, I suppose, from the libertarian perspective on this, that’s just how it goes.

The Future of Prediction Markets

The trend in gambling (or “contract purchasing,” to be technical) is in more permissive and expanded use. With that in mind, prediction markets are only likely to become more ubiquitous over time. Americans like to gamble, and, increasingly, they want to bet on more than just sports. I put some money into Kalshi this week to test it out, and it was fun. I did not “bet” anything I could not afford to lose, but it was fascinating to follow sports in real time on the platform, and also to look at some of the key political races in Maine this year, which have all types of odds (some of which I intuitively agree with, and others of which I do not).

I think what is most likely to come eventually is that the regulators will catch up with prediction markets, and tighten up on how these things are run. It may not happen immediately, though. If anything, the Trump White House has been generally permissive of prediction markets. Whereas the Biden Administration essentially banned Polymarket from operating in the U.S., the Trump Administration has eased enforcement against such entities, essentially clearing a path for Polymarket to eventually return. Richie Torres, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York, has introduced a bill that would limit federal officeholders and staff from using prediction markets, but it is unclear where this will go.

Ultimately, my belief is the prediction markets are not going away, and will probably become more prominent in the months and years ahead. Sports betting companies like DraftKings and others, are, in fact, trying to find ways to get into the prediction market space themselves, which is a fascinating twist over the past year, and evidence that the foundation underpinning any business model is subject to rapid change at any time. A year ago, prediction markets operated at the fringe of betting and academia; now they have just about become mainstream with the mainstream sports betting sites not trying to figure out how to chase them.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com. Thoughts and opinions here do not represent First National Bank.

I’m experimenting with Kalshi for the Super Bowl and I don’t mind sharing my picks with you. These are for entertainment purposes only. The real question is can I write off the losers as a business expense! Here we go:

Will Seattle win by 4.5 points or more. My pick: NO (49 cents).

Will Seattle score more than 28.5 points. My pick: NO (62 cents)

Total Points Scored over 43.5. My pick: YES (58 cents).

Drake Maye touchdown (has to be rushing or receiving; passing TD does not count for this bet). My pick: YES (24 cents).

TreVeyon Henderson 20+ rushing yards. My pick: YES (53 cents).

Will Jaxson Smith-Njigba have the most receiving yards in the game. My pick: YES (62 cents)

Will there be 2+ successful 4th down conversions. My pick: YES (54 cents)

Will the announcers say “Robert Kraft” during the broadcast. My pick: YES (89 cents).

Will Taylor Swift attend? My pick: NO (70 cents).

Will the Halftime Show last at least 14 minutes. My pick: YES (64 cents).

Will a QB win the Super Bowl MVP: My pick: YES (73 cents).

Will the Patriots win the game. My pick: YES (33 cents).

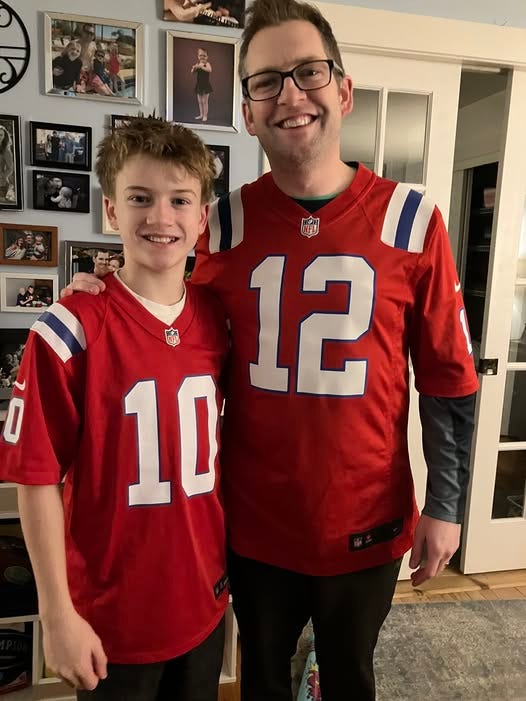

Let’s go Pats!

PBS’s Saturday night program was on this very subject, but discussing the concerns about gambling addition.