The Risks of Investing in Vacation Rentals

Welcome to The Sunday Morning Post. Check back each week for my articles on real estate, investing, and the economy. Subscribe below (for free) to get them in your inbox each Sunday morning.

Author’s Note: today’s article is not meant to offer specific advice or guidance on this type of property as an investment class. Each person’s individual circumstances are different, and there are also important distinctions between different geographic markets that investors should consider when investing in short-term rental properties. Consult with a CPA or investment advisor before making financial decisions including investments.

Today’s article is also not meant to offer a position on the appropriateness of municipal or legislative restrictions on vacation rentals.

Lastly, today’s article is meant to address the risks of vacation rentals to the investor and property owner. The risks of this type of property to neighborhoods and communities are discussed, but that is not within the specific scope of today’s piece.

The Risks of Investing in Vacation Rentals

There has been an explosion of growth in short-term rental properties over the past few years. On the demand side, the boom was fueled by the pandemic, which made many travelers wary of staying in close proximity to other people in traditional hotels. On the supply side, historically low interest rates have lent fuel to the fire, providing a boost to investors rushing to acquire homes as sources of income that were either already being operated as vacation rentals or could be easily converted.

It also seems like by the late 2010’s the vacation rental market simply reached a tipping point of consumers being more comfortable with the concept. Although AirBNB has been around since 2008, only somewhat recently did people get accustomed to the idea of staying in other people’s homes. I recently listened to a podcast series on the competition between Taco Bell and Chipotle, and one of the insights they offered is that both companies had to essentially educate the American consumer about Mexican food; these companies knew they had a great product, Americans just didn’t understand or want it yet. So too has it been with companies like AirBNB, VRBO, and a plethora of other upstarts that have been working over the last two decades to get Americans comfortable with staying in each other’s homes (and RVs, and cabins, and treehouses).

It seems that the necessary comfort level has now been reached. According to one study, there are nearly 2 million vacation rental units nationwide. The same study reports that 81% of Gen Z has already stayed in a vacation rental property, a much higher percentage than among older cohorts. According to research group AirDNA, the Average Daily Rate (ADR) for a vacation rental property is forecasted to be $286.91 in 2023, up from $260.97 in 2021 and up from $214.30 pre-pandemic in 2019. When you take a $286.91 ADR and multiply it by a 30-day month, at $8,607/month it is not hard to understand why so many Americans are converting properties to short-term rentals, including a lot of existing rental property owners who are seeing greater revenues month-to-month filling their units with short-term stays instead of long-term tenants. So too are many homeowners, who are now choosing to rent out in-law apartments, basements and attics and spare rooms, or their full homes in pursuit of what appears to be readily-available income from short-term guests.

So, great income potential with an increasingly savvy user-base growing more comfortable with the product with each passing year. What’s not to like? I do not dispute that vacation rentals have been a great investment for many over the past few years, and likely will continue to be so for years into the future. But, as I frequently say in these articles, good investors need to constantly challenge their assumptions, think long-term about all types of risks, and prepare for a changing economic environment that could disrupt their business models. In other words, you need to prepare for the downtimes when times are good. And with regard to vacation rentals, significant risks abound.

Risk #1 — Oversaturation

There is a longstanding joke in economics that if an economist is walking down the street and sees a $10 bill on the ground, he or she won’t pick it up because it would not actually be there. The joke is that in a capitalist system, profit opportunities are often only temporary because the market adjusts as other participants rush in to take advantage. In the mind of an economist, there should never be a $10 bill lying on the ground because someone would have already taken it.

Oil wells, gold mines, lumber prices, burritos, used cars: whatever good or service you want to think of, if the existing players are making easy money with it, others are going to swoop in and take advantage of the opportunity, which eventually is going to level out both prices and profit for everyone. From a consumer’s perspective, this is good because increased competition usually leads to lower prices. But from a seller/producer’s standpoint, the benefits of being first on the scene or early to an investment trend are eventually watered down as time goes by. These benefits may even vanish altogether if too many competitors jump in. Keeping in mind there are entire volumes of economics textbooks that talk about inefficient markets, monopolies, asymmetric information, and any one of a number of other variables that show how and why markets are often not completely efficient, this is still a pretty good framework for understanding why something that is or was profitable may not be that way forever.

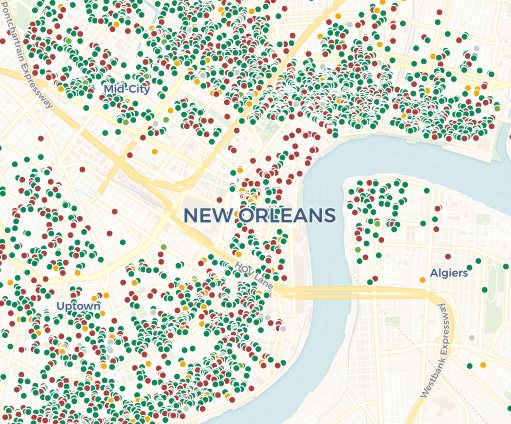

Now, with regard to vacation rentals, the top risk I see in this investment class is that eventually there will be too many vacation rental properties for consumers to choose from. Some markets may already have reached this point. Consider the map below of New Orleans, which shows various types of short-term rental units. Admittedly not knowing a lot about New Orleans myself, this feels like an oversaturated market.

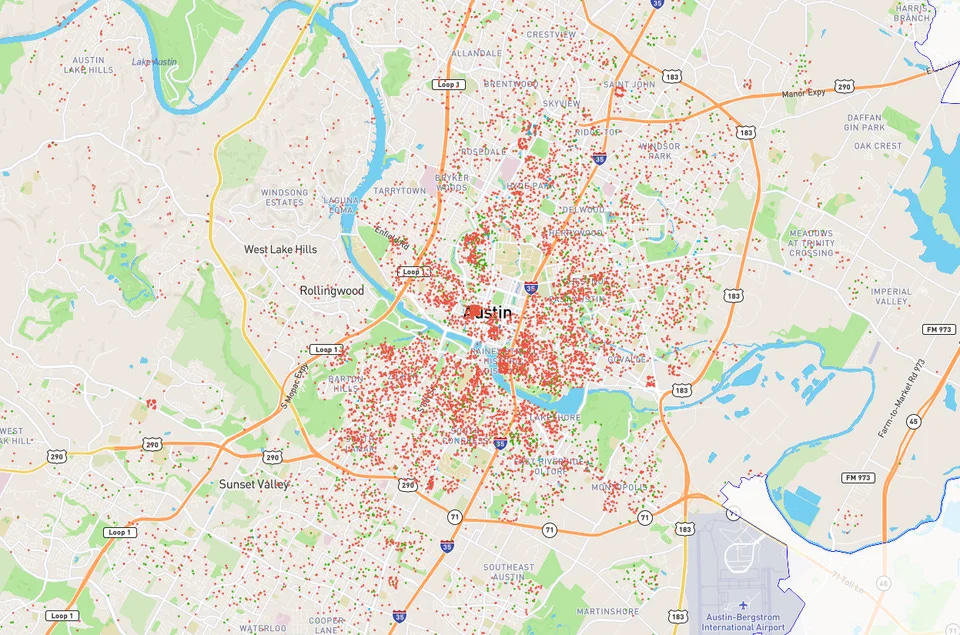

A similar map below shows the thousands of AirBNB units currently listed (as of seven months ago, the date of the map) in Austin, Texas:

The risks to the real estate investor (to say nothing of the risks to the community, which I will expound upon a bit below) are clear: at a certain point, just like with an oil field with too many pump jacks in it, there’s not enough juice left for everybody. What it will look like in some of these communities is greater vacancy rates as a result of surplus supply of available units, depressed prices as consumers have more choices of where to rent, and tighter margins for investors if not outright losses. Yes, Virginia, you actually can lose money as a real estate investor. If there are more short-term rental units available than people who want to rent them, there will be losses for some (or at least flatter margins). And if growth trends continue including thousands of American homeowners choosing to rent their homes out as short-term rentals (made all the more common by homeowners wanting to keep their properties with 3.00% interest rates or better instead of selling them once they move), this supply vs. demand mismatch may become evident sooner rather than later.

Risk #2 — Regulatory

The other major risk to rental property investors is that, in fact, not everyone likes them. Consider the example of Austin, Texas, as noted above with reference to the map of AirBNB units. A recent article in Texas Monthly reports on the conversion of a number of historical single-family homes in Austin that have been changed into trendy vacation rental spots, including one described as such:

Since the home was posted on AirBNB, neighbors have watched it become a go-to destination for live-streamed product launch parties, group retreats, and rowdy bachelor and bachelorette parties. The revelers typically arrive every few days from around the country, paying hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars per night (often with a three-night minimum). One neighbor came up with a label for the packs of shirtless young men who arrive in party buses and come and go on electric scooters, carrying cases of alcohol, vomiting in the street, peeing in the bushes, and partying into the early morning hours week after week: “monetized nuisance.”

People generally do not like to see their communities change, and considering the example above who can blame them. Every time a home is converted from a single-family residence or a long-term rental with a stable tenant, it changes the character of that block, which can change a neighborhood, which, of course, can change a community.

And it is not just the nuisance factor that matters. As noted in the Texas Monthly article, property taxes often rise in these neighborhoods as the values of the homes are actually greater once monetized in this manner. And, of course, the overarching problem is that the loss of these homes as actual homes or long-term rentals is a significant contributor to the housing crunch so many of these cities (and indeed, nationwide) are experiencing. Every property that is operated as a short-term rental is one less home for the proverbial nice-young-family, a retiree, or an employee working at the local restaurant, manufacturing plant, or wherever.

All of this has the attention of policymakers including city councils and state legislative bodies in town halls and state houses around the country. The actions that are brewing among these communities nationwide are almost too plentiful to name at this point. The following is just a small sampling:

In Santa Monica, California, the host must be present during the guest’s stay. The host must also register as a business with the city, and collect a local 14% occupancy tax that goes to the city. These changes were estimated to have eliminated 80% of short-term rental arrangements in Santa Monica.

In New York City, it is illegal to rent a unit of any kind for less than 30 days without the host present.

Honolulu, Hawaii banned rental stays that are less than 90 days.

In Burlington, Vermont, hosts must live in the property they are renting out, and must also pay a 9% revenue tax.

Coeur D’Alene, Idaho has stopped permitting for any new short-term rental units, and is requiring permits to be obtained for any rentals less than 14 days.

In Marco Island, Florida, hosts must have a $1 million liability insurance policy, must provide a phone number to city officials that will be answered 24 hours a day, and are subject to other fees and restrictions.

Restrictions are not limited only to the United States. In Paris, France, you can only rent out a unit if it is part of your personal residence, and even then only for a maximum of 120 days per year. In London, you can not rent out a short-term rental for more than 90 days per year. These types of limits are, I believe, in general recognition that for many homeowners, renting out a portion of their homes including an in-law apartment or what is commonly known as an ADU (accessory dwelling unit), is actually a very helpful and positive source of income, especially for those who are retired and living on a fixed income or struggling to keep up with the costs of owning their homes. But the restrictions also significantly tamper down the ability of homeowners to freely rent their properties without limitation.

The list above would go on and on. There are dozens if not hundreds of communities around the country that either have or are considering restrictions on short-term rentals. This includes a community close to home for me: Bar Harbor, Maine. I wrote about the Bar Harbor story in November 2021. Bar Harbor, which stands at the doorstep of Acadia National Park, is one of the most visited communities in the country during the summer months. In 2021, its voters approved various measures that would restrict short-term rental activity. These changes included limiting the number of short-term rentals to 9% of the total housing stock and determining that once a property is sold, its short-term rental permit is not carried through to the subsequent owner, which will steadily draw down the number of permits over the course of time through the natural attrition of property turnover. These are big changes, and have already fundamentally changed the short-term rental situation in the community. You can read my previous article on the topic here.

For investors, the regulatory environment and the general temperature of things are crucial to understand. The momentum nationwide right now in hundreds of communities ranging in size from Millinocket, Maine (population 4,200) to New York City (population 8.5 million), is towards increased regulation, greater restrictions, and heavier taxes on this type of activity. Some investors are aware of this. I spoke with one client recently who focuses on long-term rental properties, as many real estate investors do, as opposed to short-term rentals. On the question of whether he was converting any of his units to short-term rentals to take advantage of the profit boom he said, “No. I would never let my business model risk being impacted so significantly by what three selectmen in [town name removed for the sake of confidentiality] say I can do with my property.” In a lot of small towns with only five members of the board of selectmen, it really would only take three to significantly change things (planning boards, appeals processes, and legal challenges, aside).

The Other Risks

All of the usual risks when considering vacation rentals are relevant too, including the problem of difficult and rowdy tenants, the costs of repairs and renovations, and the time and expense of turning properties over every few days. An additional risk I would throw in for consideration is the rapid rise in interest rates. For property owners who are financing their acquisitions, which is the majority of them, properties just do not cash flow as well when the financing has an interest rate that begins with a 7 or an 8 as they did when the interest rate began with a 3 or a 4, which was not that long ago.

Nonetheless, for today I wanted to focus on what I see as the two most significant risks, which also happen to be ones that I think many rental property investors do not give full consideration to: oversaturation and regulatory risk. I do not want people to take as a conclusion that I am saying short-term rental properties are good or bad, per se; as noted above, short-term rentals can provide crucially important income streams to property owners who need it, not to mention the tourism dollars visitors bring to communities that may be underserved by traditional hotel offerings. Investors can and do also invest significant sums of money to rehab properties that might otherwise fall into disrepair, which can be beneficial for local communities. But in writing today’s article, I just want to offer people my perspective: there are these unforeseen and fairly significant risks lurking to the investor that they should be mindful of even during a period of time when profits are high and ambitions are lofty as they are now.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com. Follow Ben on Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. Opinions and analysis do not represent First National Bank. © Ben Sprague 2023.