The Supply and Demand Loan Divergence

There’s a funny concept in banking: the more you need the money, the less the bank wants to give it to you. On the other hand, if you don’t really need to borrow, banks will be lining up to lend to you.

One of the most common questions I get as a banker is, “What are you seeing out there?” I hear this almost every day in conversations with bank customers, business owners, realtors, attorneys—or even just in line at Bagel Central or Chipotle. And lately, what I’m seeing is a divergence in the typical interplay between borrowers and banks: people don’t want to borrow, and banks don’t want to lend to them anyway.

So what’s going on?

On the demand side, interest in borrowing is at an all-time low in various loan categories. Part of the reason is uncertainty about the economy, but the main drivers, of course, are high interest rates and elevated prices. The orange line in the chart below shows the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate nationwide over the past ten years, while the blue section shows data from the Mortgage Bankers Association on home loan applications. As you can see, the two variables are inversely correlated—that is, when rates go up, mortgage applications go down, and vice versa.

Unsurprisingly, the chart for home refinances (i.e., not new purchases but the refinancing of existing loans) mirrors the chart above. Refinance activity is nearly nonexistent these days because very few homeowners have interest rates high enough to justify a refinance. This has left the hallways of residential lending offices particularly quiet.

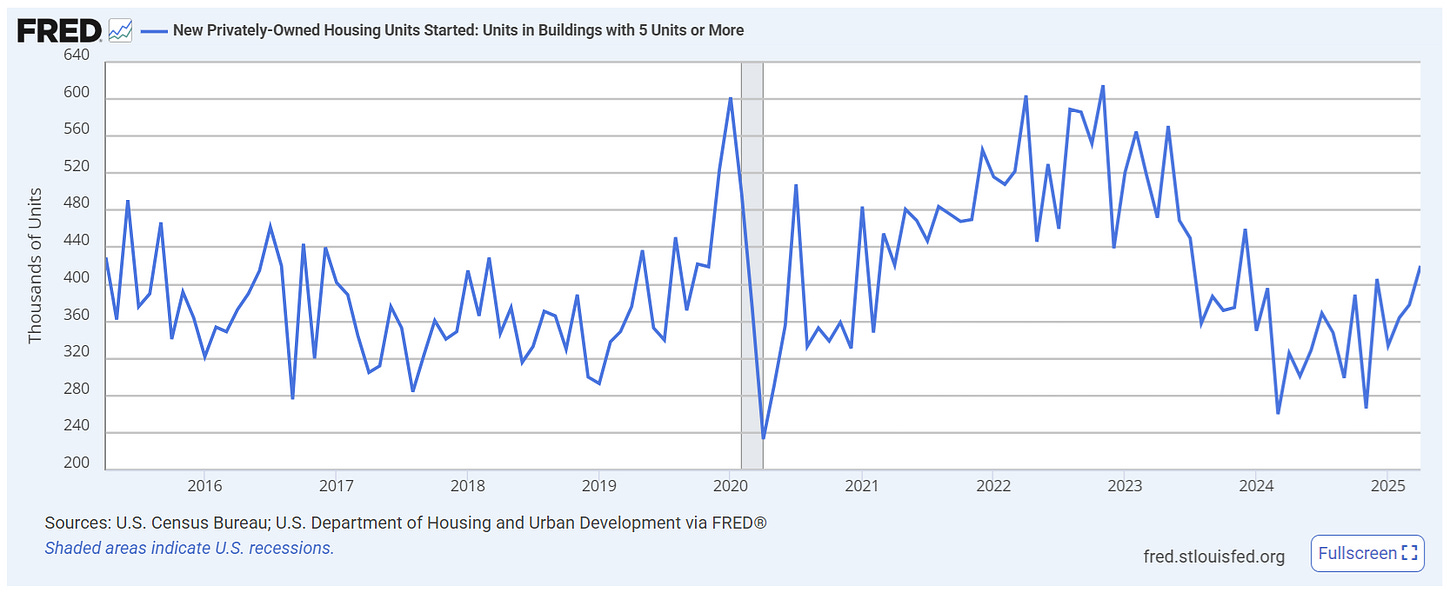

What about other types of debt beyond homes? There’s some evidence that multi-unit construction is ticking back up after bottoming out in the second half of 2024. The chart below shows construction running at an annualized, seasonally adjusted rate of 420,000 new units per year as of April—up from 2024 lows, but still down notably from 2020–2023. That current pace is roughly in line with pre-pandemic levels.

Still, commercial borrowing overall isn’t much stronger than residential. Both remain slow as developers continue to pause new projects due to the financial math and a general sense of uncertainty.

One especially interesting data source on lending conditions is the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices, or SLOOS for short. The April SLOOS (released in May) showed its 12th straight quarter of reduced demand. This trend holds true for both commercial real estate loans and commercial construction/land development loans. On the residential side, demand has now declined for 16 straight quarters.

What About the Supply Side?

In an efficient market, if demand is low, the supply side typically adjusts by lowering prices to find an equilibrium. For example, if nobody wants a Nintendo Switch at $800, the company might have to lower the price to $500 to spur sales (I am pulling numbers out of the sky here, by the way).

But there is another way supply can respond: by simply not producing the good or service. If it costs $550 to build a Switch between the parts, labor, and shipping, it wouldn’t make sense to sell it for $500—the company might as well just stop making them.

Something similar is happening in banking right now. Banks aren’t slashing interest rates to meet borrowers where they are. Instead, they’re just not lending as much. In fact, the same SLOOS report showing 12 straight quarters of reduced demand also revealed 13 straight quarters of tightening credit standards for commercial loans, including multi-unit rental property loans. Standards haven’t tightened quite as sharply for home loans, but they certainly haven’t eased.

In short, even as demand declines, banks are responding by becoming more selective—tightening standards rather than loosening them.

Why Are Banks So Tight?

There are several reasons banks are cautious right now, many of which have little to do with traditional supply and demand. For starters, banks are in the business of managing risk—and right now, the economic outlook is uncertain. Many banks are simply waiting it out.

A common theme in lending circles is that banks do not want to let borrowers become overleveraged. In an environment with higher rates and increasing pressure on consumers and as the labor market tightens, banks are wary of borrowers ending up on the wrong side of their monthly payments.

The story is more complicated with home loans, however. In commercial lending, banks usually keep loans in-house. But on the residential side, it’s different. Most banks package their home loans for resale, which are then bundled into collateralized debt. Consumers may not like to think about their home loans being sold and re-sold, but that’s how the mortgage market works.

In today’s interest rate environment, investors can get a 4.5% yield from a 10-year U.S. Treasury note—essentially risk-free. That’s where the market closed this past Friday. So why would an investor want to buy a 4.5% mortgage-backed security, which carries more risk (see: 2008)? As a result, banks have to “price in” that risk by offering mortgages at even higher rates to attract investor interest in the re-sale market. This flips the typical supply-demand dynamic on its head: investor demand (rather than consumer demand) is what sets the price in the market for packaged home loans.

Pricing home loans is not an exact science. Each bank has different risk tolerances and can be more or less aggressive at different times. But historically, mortgage rates are priced as a spread above a benchmark—often the 10-year Treasury yield. A typical spread is 2–3%. So if the 10-year Treasury is at 4.5% (as it is today), mortgage rates will typically range from 6.5% to 7.5%, which is exactly where they are.

For related context, the 10-year Treasury yield dropped to just over 0.5% during the early pandemic in 2020, which is why mortgage rates at that time were in the 2.5% to 3% range, a once in a generation opportunity for so many existing and would-be homeowners.

What It Means for the Economy

It may seem odd that banks wouldn’t want to lend—but banks aren’t public utilities. They’re corporations, and they make decisions based on many variables, including profitability. And lending isn’t the only way banks can make money or allocate assets, so at this moment in time, lending is tight while the focus is on other areas.

As for the broader economy, the current divergence—borrowers not wanting to borrow, and banks not wanting to lend—isn’t healthy in the long run. Hopefully, this gap will close as interest rates begin to tick downward. When people aren’t buying homes or vehicles or making other major life decisions, and when businesses aren’t borrowing to expand or hire, it slows economic growth. A single home loan, for example, can generate economic activity for a wide range of people: real estate agents, title attorneys, appraisers, inspectors, contractors, and suppliers. When lending slows, all of that downstream activity slows too, dragging the broader economy with it. We are a moment in time where a lot of the economic activity that is meant to happen is frozen, which could become pent-up and lead to contraction, but then a burst at some point down the line as the normal business cycle resumes.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

Appreciate your perspective and look forward to reading more! I’d love to hear about other components of the bank balance sheet outside of home loans.

(The SBA arb is pretty neat!)