The Surprise Item No Longer Inflating: Rents

The most recent Consumer Price Index report showed inflation running at a 3.0% clip year-over-year through September. Inflation is down from its 2022-2023 peaks, but still above the Fed’s stated goal of 2.0%. The biggest risers in the September report were utilities (electricity + 5.1%; piped gas service + 11.7%) and used cars and trucks (+5.1%). Gasoline, fuel oil, and apparel were all down.

At least on paper, the CPI report has rents increasing year-over-year by 3.4%. But other methodologies have rents essentially flat or even on the decline, particularly in certain markets. I tend to put more faith in the other methodologies, mostly because they are able to capture data in real-time, whereas the CPI report is done through manual surveys, and the data analysis often has a time lag to it.

Zillow, in its own report on the state of the rental market through September, noted rents in multifamily properties had increased year-over-year at a pace of just 1.7%, the smallest increase Zillow had found since 2021. Zillow also noted that 37% of landlords are offering concessions on rents, a September record. Certain markets are seeing notable rent declines. Per the report:

Apartment rents are falling fastest year over year in Austin (-4.7%), Denver (-3.4%), San Antonio (2.3%), Phoenix (-2.2%), and Orlando (-0.8%). Higher rent growth is centered in areas with stricter building codes and in high-demand, relatively affordable areas, led by Chicago (6%), San Francisco (5.6%), New York (5.3%), Providence (4.8%), and Cleveland (4.2%).

For more on the Austin story, you can read my previous article on the market. Essentially, rents are dropping there so significantly because of heavy construction of new units. Tenants in Austin now have many more options from all the new units that have come online, which is softening prices. This is a good lesson for municipal policymakers and housing advocates in other parts of the country, as well: the surest way to bring down rents, which is a worthy policy goal, is to support robust construction of new units.

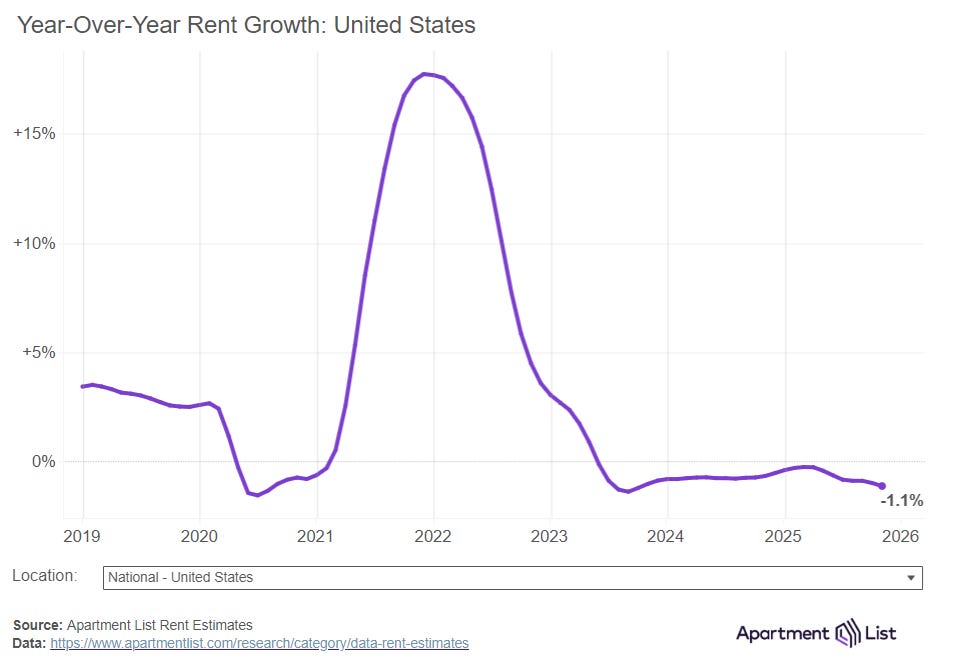

Other research firms and media outlets are finding the same thing as Zillow: rents are softening. Per calculations in the Apartment List Rent Report, rents are down about 1% year-over-year. Apartment List has actually seen rents declining for over two years now, as evidenced in the chart below, in which the surge of rents during the pandemic is clearly evident:

The main reason for the cool-off in rents, per Apartment List, is the huge boost in the construction of multiunit rental units over the past few years. They report:

As a result of all this new inventory, more vacant units are sitting on the market, meaning that property owners face more competition for renters and have less pricing leverage. Our national vacancy index – which measures the average vacancy rate of stabilized properties in our marketplace – sits at 7.2% in November. This represents an all-time high for this data series, going back to the start of 2017…At the same time, a shaky labor market seems to be putting a damper on housing demand, another factor contributing to sluggish rental market conditions persisting longer than we anticipated at the outset of this year.

In its own rent report, Realtor.com found rents were down 1.7% year-over-year in October, which marked 27 months of year-over-year declines in rents, which even to a close observer of the rental market like me feels surprising and significant. Like Zillow and Apartment List, Realtor.com attributes the drop to the increase in new construction, with a nod to an uncertain economy softening things up in general.

What it All Means

For many renters, the statistics referenced above are welcome relief. That said, it takes awhile for people to internalize slow-moving changes. It is not like prices have fallen off a cliff, suddenly 20-30% lower. In fact, by the CPI metric, rents have continued to actually rise. Others, like Zillow, have rents essentially flat. The Realtor.com report does have rents down 3.6% since the summer of 2023, which was the rent price peak. In that same time, incomes nationwide have generally risen, up about 7% in that two-year period. People might not feel that delta between their incomes and what they are paying in rents quite yet, but there is some evidence that it is there.

For rental property owners, this continues to be a tale of caution. While income from renting out properties is leveling off and maybe even dropping in some markets, the expenses of property ownership continue to rise — insurance, most notably, but also property taxes, the cost of repairs, and utilities. These increases come on top of a higher cost of borrowing. Interest rates have come down a bit over the past 12 months, but they are still quite elevated compared to what we saw in 2020-2022.

All of this puts pressure on the mom-and-pop landlords out there, and the like. I have seen many a business plan and pro forma come across my desk from people wanting to get into the rental property business that calls for increasing rents 3-5% per year. That looks good on paper, but ultimately you can only increase rents to a level that the market will bear.

Right now, the market is changing, with much of the leverage moving from property owners and landlords to renters, who have more units to choose from with the new construction that has come online over the past 2-3 years. The pace of that new construction is leveling off a bit, which is a topic I plan to come back to in January with my rental market preview article for 2026 (along the lines of what I have written in 2025, 2024, and 2023), so it feels like maybe we are going to hit some sort of equilibrium at some point where the forces of supply and demand meet each other partway. Time will tell. For now, much like we have seen in the housing market, some of the froth and fizziness in the rental market has subsided, although, to be sure, many renters continue to live very close to the line, in part because so many of the other expenses of daily life have also continued to rise.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. Ben can be reached at ben.sprague@thefirst.com or bsprague1@gmail.com.

My landlords had advised of a 10% increase.

Waterville has recently had 70 +_ apartments available for rent. A year ago, when I checked the online listings, there would be fewer than 10 listings. There are many new units for low to moderate incomes coming online in the near future.

I’m surprised that there has been such a dramatic shift when these new units have not yet opened. Perhaps because landlords began to charge both first and last months rent and a deposit? That may have priced out new renters as units became available.