When Will Interest Rates Go Down?

The Federal Reserve hiked interest rates yet again this week by another quarter point as they continue their hawkish stance against inflation. This is despite the fact that inflation is now running at 3.0% based on June data, the lowest rate of inflation in over two years. The Fed’s stated goal for inflation is for it to run at a 2% annual clip, so we are not too far off at this point.

Why is the Fed continuing to raise rates? Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has been clear for the past year that they see a risk of inflation remaining stubbornly high or even rebounding once it was thought to be quelled. Like a firefighter monitoring the embers of a dying fire to make sure it does not roar back to life, so too does the Federal Reserve preside over the sputtering death of the latest inflationary cycle. The winds that could give these soft glowing embers the life they need include a robust labor market, rising wages, and strong consumer spending, all of which are at play at this point.

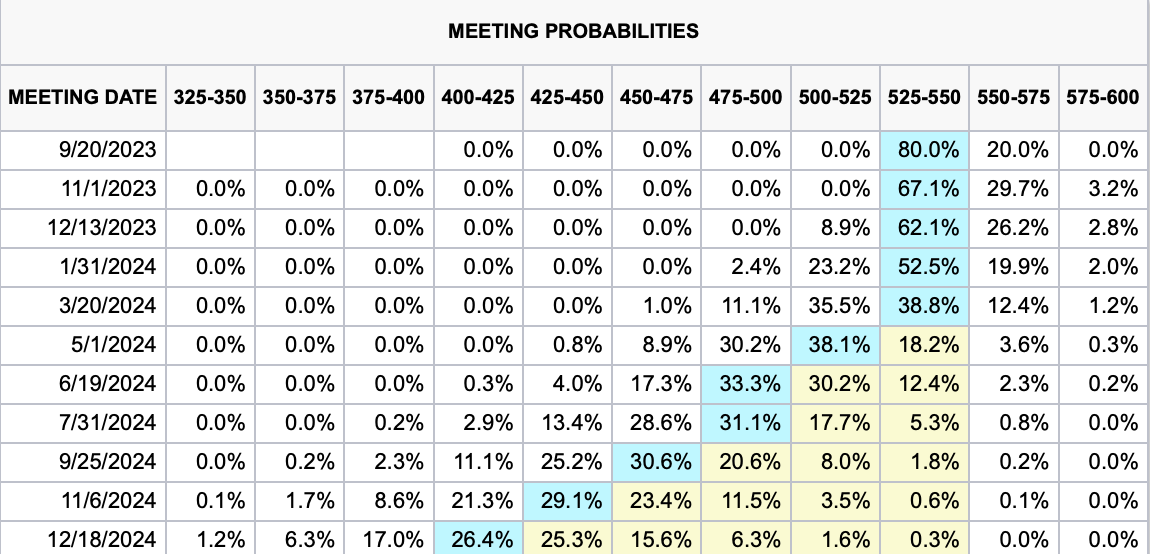

Borrowing costs are now the highest they have been since January 2001, which begs the question, when will interest rates start going down? Economists and various market players have different predictions. The CME FedWatch Tool, which aggregates projections from various sources, pegs the chance the Fed will not hike rates at their September meeting at 80%, with a 20% chance they will increase rates again. No one is projecting rate cuts by September.

What about by the end of the year? Well, that is where the possibility of rate cuts start to enter the picture. The chart below shows a 62.1% chance that rates end the year where they are now, a 26.2% chance they are marginally higher, a 2.8% chance they are significantly higher, but an 8.9% chance they are lower:

The chart below is pretty quantitative, but essentially it shows the projections for rate ranges at each of the Fed’s various meeting dates through December 2024. Rates currently are in the 525-550 range (5.25-5.50% for the Fed Funds rate). You can see the most likely rate option in each of the blue boxes; their movement downward to the left reflects projections that rates will decline steadily from March 2024 onward.

The chart below shows the same basic data in a different format: the first time when the likelihood of a rate decline from where we are today is greater than the likelihood of either a rate hike or staying put is at the Fed’s May 2024 meeting, at which point economists give a 77.95% chance that rates will ease relative to where they are today.

Where does that leave things today? The data above suggests that borrowers are likely facing one more rate hike this year, although there are reasonable chances that there are 1) no further rate changes or, on the other side of the coin, 2) there are two more rate hikes. Either way, rates are not likely to come down in the immediate months to come.

On the residential front, the most optimistic analysis I have seen about rate cuts is from Morningstar, which says:

We expect the Fed to pause its rate hikes after having conducted its final hike in July 2023. Then, starting around the beginning of 2024 (we expect in the first meeting in February 2024), we expect the Fed to begin cutting the fed-funds rate. The Fed will pivot to monetary easing as inflation falls back to its 2% target and the need to shore up economic growth becomes a top concern…

…We project price pressures to swing from inflationary to deflationary in 2023 and following years, owing greatly to the unwinding of price spikes caused by supply constraints in durables, energy, and other areas. This will make the Fed’s job of curtailing inflation much easier. In fact, we think the Fed will overshoot its goal, with inflation averaging 1.8% over 2024-27.

I have to say that even though this analysis has been panned in some circles as excessively optimistic, I tend to agree with it. The primary reason I see rates going down sooner is because of lag effects at play in the inflation data. Housing, for example, represents a key component of the overall CPI figure, and housing prices have remained elevated. But there is now evidence that rents in many parts of the country are leveling out and even starting to decline in some areas (more on this in a future article). Home prices have also moderated. Once this reality on the ground catches up in the data, which can lag by several months, overall CPI will continue to ease.

There is also the lag effects of what the sharply higher interest rates are doing to the economy. Yes, the labor market remains strong and consumer spending is brisk, but eventually the impact from the rising rates is going to be felt. Credit card rates, for example, are extremely high. Eventually that is going to catch up with consumers. And home sales are way down. I’ve written about this before, but the ripple effects alone in spending from a single home sale are significant: renovation costs and contractor bills, materials, real estate commissions, title work and bank activity, etc - there is a lot of spending that goes into a home transaction. With transactions being down over 20% (largely due to the higher interest rates), this chokes off a large amount of economic activity, thus not generating those aforementioned ripples. The economy will start to feel this soon, to mention the impact of less borrowing for big ticket items like cars.

Morningstar presents a pretty rosy picture of home interest rates by 2025, projecting that the average 30-year fixed rate drops back to 4.50% from its current level north of 6.50%. True, that is two years out and a lot of would-be buyers are running out of patience with the twin headaches of high prices and high interest rates, but for those who can be patient, if Morningstar’s analysis is correct, there will be relief for borrowers by 2025. In my opinion, money was far too cheap for several years, and now it is too expensive. Getting back to a 30-year fixed rate in the 4.50-5.00% range would be healthy for the economy. Commercial rates would be likely correlated to those residential rates, albeit it at a typical 0.75-1.25% premium over the residential number. This would be welcome news to commercial borrowers.

Lastly, and this, too, is likely the subject of a future article, there are always unanticipated consequences to government intervention in certain areas. True, the Fed has been able to thread the needle pretty well so far in reining in inflation without the bottom falling out of the labor market (or the stock market, for that matter), but there is something wrong with the housing market right now. People are not moving, in large part because they do not want to give up their pre-2021 interest rates. For lack of inventory, home prices have continued to rise. If the Fed wants to jolt the housing market and actually loosen things up, they should significantly cut interest rates. Once home mortgage rates go down, there will be a rush of new listings as sellers no longer have to feel squeamish about giving up their good rates. At some point, there will be a huge inventory surge, and this massive bump in supply will actually help to lower prices by providing buyers with many more options and therefore more leverage in negotiations. But that may still be a year or two out. Sellers should be mindful to get out ahead of that if life circumstances allow. The best course of action would be to sell now, live without a mortgage for a year or two either by renting or through some other arrangement, and then buy once a glut of new supply hits the market 18-24 months from now and both prices and interest rates have eased off a bit.

Ben Sprague lives and works in Bangor, Maine as a Senior V.P./Commercial Lending Officer for Damariscotta-based First National Bank. He previously worked as an investment advisor and graduated from Harvard University in 2006. © Ben Sprague 2023.

Weekly Round-Up

Here are a few things that caught my eye this week that might interest you too:

A tiny four-branch bank in Kansas has failed, making it the fourth U.S. bank to do so this year (although by far the smallest). There is little word yet on why the bank went under, but the reading I have done suggests it may have been due more to isolated fraudulent activity and not systematic risk. The FDIC seized the bank on Wednesday and it has since entered an agreement with another Kansas-based community bank to take over. Read more.

More from Morningstar (via Lance Lambert), just 3.7% of home mortgages are at a rate above 6.00%. The vast majority of U.S. homes have either no mortgage or a rate in the 3.00%-4.00% range or below.

CarDealershipGuy on Twitter, who I have found to be an interesting source of news and data on the auto industry, has a list of the cars currently selling for the biggest discounts. Read more here. Top on the list? Two Alfa Romeos (whatever that is), and then a Kia, Mazda, Jeep, and Buick.

I was quoted in an article in The Atlantic by Charlie Warzel on the antiquated quaintness of phone numbers. You can read the article here. Here in Maine, the entire state is still, believe it not, the same area code: 207. I’ve had many a friend who has moved to Maine oftentimes for professional reasons who have expressed frustration that they do not want to give up their previous phone number, but they feel like they never quite fit in (and are constantly judged) as a result of their non-207 numbers. I expect that phenomenon will fade over time, and there is even talk that Maine might need to expand beyond its 207 area code as we may be actually running out of numbers (we have until 2029), but for now, I, too, appreciate the anchoring and nostalgia of a good, solid 207 number (even if I do feel bad for those people “from away” who suffer the sometimes subtle and occasionally overt judgement of us 207-originals.

Have a great week, everybody!